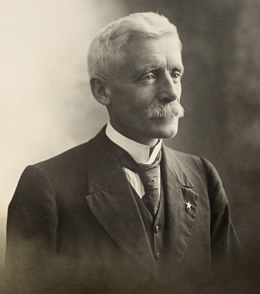

REID, Matthew (1856–1947)

Senator for Queensland, 1917–35 (Nationalist Party; United Australia Party)

Matthew Reid was born at Dalmellington, Ayrshire, Scotland, on 30 September 1856; only the name of his mother, Elizabeth Reid, is known. In his early years Reid worked as a carpenter, serving his apprenticeship in Glasgow and working in London, where he married Mary Smart on 24 June 1879. He joined the Amalgamated Carpenters’ Union, and was a member of Henry Hyndman’s Social Democratic Federation, which preached a type of Marxist socialism and numbered Tom Mann among its members. Reid arrived in Brisbane in 1887. He intended to farm, but instead soon became active in trade union circles. A delegate to the Trades and Labour Council, in 1889 he was elected as a member of the council’s successor, the Brisbane District Council of the Australian Labour Federation (ALF). He was a member of the first Board of Trustees of the Worker and in 1892 elected to the executive council of the Queensland Labor Party. He was a leading organiser for the labour cause.[1]

From late 1892 Reid was working for the election of himself and other Labor candidates to the Queensland Parliament. In 1893 he was successful, narrowly defeating the Postmaster-General and Minister for Railways, Theodore Unmack, for the Brisbane seat of Toowong. In 1896 Reid lost the seat, by seven votes, to draper Thomas Finney. In a by-election later that year, he unsuccessfully contested the seat of Logan. It was in this campaign that he was introduced to a meeting at Logan Village by a farmer of German descent as a ‘Labour alligator’. In 1899 Reid was again defeated in Toowong, but won the seat of Enoggera at a by-election in December. He lost Enoggera in 1902, and was defeated again for Toowong in 1904 and for Burrum in a by-election in 1905. Nevertheless, even his opponents recognised his undoubted ability. On the occasion of his defeat in 1896, the Brisbane Courier said of Reid:

Political work awaits him in the future if he will take shorter and more sensible views of what Parliament is able to do in furthering the development of the Australian nation . . . He is a strong man, but the misfortune is that he has allied himself with a weak policy. What many of his present political opponents wish for him is a speedy deliverance from belief in Socialism.[2]

During his time in the Queensland Parliament, Reid proved a strong advocate of White Australia and democratic reform. He sought change in the sugar industry, but feared the Pacific Islanders would be replaced by other races, describing Indians as ‘the most filthy, dirty, race of men that I ever came across’. Although he enjoyed his reputation as a ‘professional agitator’, he was opposed to strikes. He urged the Government to settle the seamen’s strike of 1893 and the shearers’ strike of 1894, and supported calls for the introduction of arbitration legislation. The Government responded with the Peace Preservation Bill (dubbed the ‘Coercion Bill’) and Reid became one of seven Labor members suspended from the Legislative Assembly during a chaotic debate. Along with two other members, Reid took out writs against the Speaker claiming damages for assault, trespass and false imprisonment, but the Supreme Court ruled, and the Full Court later confirmed, that Parliament’s conduct of its internal affairs was not subject to the courts. Public subscription raised £269.13.4 for Reid’s costs. In 1895, he participated in an attempt to settle the Brisbane boot strike. The experience confirmed his belief in the need for arbitration legislation.[3]

Reid saw arbitration as a palliative only. ‘He was himself a Socialist’, he told a meeting at Beenleigh in 1898, ‘and had never denied it’. He believed ‘in socialism pure and simple’. ‘The only way to do away with strikes’, he argued, ‘is to give the labourer a fair share of the wealth he creates’. Likewise, his criticism of other measures was ‘that they only go half-way’. Protection, for example, was ‘only spurious socialism’, which used ‘the power of the Government to increase the power of the employer’. Reid liked always to be against the Government, whatever its complexion. In 1893 he stated: ‘I am not so very anxious to put the present Government out, because I am of opinion that Governments are all bad alike’. In 1894 he trusted ‘that my principles will always keep as unbending as now, and that instead of being in any Government, I shall always be “agin the Government”’. Even in 1898 he did not believe Labor was ready to govern. The experience of the Dawson Government in 1899 confirmed Reid’s views. He remained an inveterate opponent of coalition.[4]

It was outside Parliament, however, that Reid and his unbending principles made their real mark upon the early development of the labour movement. He represented the Brisbane District Council of the ALF at the Labor-in-Politics Convention of 1892, and was elected to the executive council of the Labor Party, later becoming treasurer. In 1895 he was elected to the central political executive (successor to the executive council). Throughout the 1890s he campaigned tirelessly on behalf of both the ALF and the Labor Party, working to maintain and strengthen the Labor organisation, and gaining a reputation as Labor’s hard man.

Reid returned to the central parliamentary executive in 1903 and in 1905 was elected president. At the Labor-in-Politics Convention in May 1905 he engineered the adoption of the goal of collective ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange—the socialist objective—and let it be known to the parliamentarians that no compromise would be entertained. By 1907 he was at the peak of his power. He had opposed the parliamentary coalition with Sir Arthur Morgan in 1903, but had agreed to abide by the party’s decision. At the fifth Labor-in-Politics Convention (1907), he threw down the gauntlet to his parliamentary colleagues: ‘Labour’s path, as in the past, is straight ahead—no swerving to the side or turning back. Whatever troubles or suffering may lie before us we have to tread that path alone’. Reid had the satisfaction of seeing the convention vote to throw aside the fetters of coalition, even though the Government was now led by Labor’s William Kidston.[5]

The result was the first great Labor split in Queensland, a large majority of Labor parliamentarians following Kidston out of the party. Reid denounced Kidston as a reactionary and in turn was labelled ‘the high priest of the extremist camp’. Labor was routed at the subsequent elections, winning only eighteen seats. Reid’s last months as a force in the Labor Party were not happy ones. Many blamed him for the split and the subsequent electoral failure, and a new generation of leaders, less mindful of Reid’s contribution to the movement, was emerging. In 1909 the executive, against Reid’s wishes, endorsed the maverick Joe Lesina as a candidate for the forthcoming election. Reid resigned from the executive, bringing to a close two decades of hard, and often unrewarding, work on behalf of Labor in Queensland.[6]

The personal cost had at times been high. Unable to get work in the building industry because of his political activities, Reid turned to tailoring following his defeat in 1896. By 1900 he had established his own business in central Brisbane (his opponents in the Assembly made much of his new-found status as an employer, calling Reid ‘the sweating tailor’). Unable to get work as a paid organiser following his defeat in 1902, he remained in business until his return to the political arena in 1917.[7]

If the disillusionment of his final years as a labour leader marked the beginning of Reid’s journey beyond the labour fold, a new intellectual enthusiasm characterised the next stage of that journey. In 1908 Reid joined the Theosophical Society and throughout his subsequent parliamentary career managed to find time for theosophical work, running a study class on Annie Besant’s A Study in Consciousness, and giving public lectures on theosophy. He provided Besant with material on the Australian Constitution, which she used in framing her Commonwealth of India Bill, and facilitated her entry to Australia. In June 1922 he organised the attendance, in the midst of an election campaign, of Prime Minister Hughes at a Besant lecture on ‘India and the Policy of a White Australia’. It would seem that Reid found in theosophy what he had sought in the secular religion of socialism. At the time of his death, he was the oldest Queensland member of the Theosophical Society.[8]

Although maintaining his advocacy of White Australia, Reid’s theosophical activity was the catalyst for a profound change in his attitude towards race, which led in turn to a deep interest in the affairs of India. Contrary to his earlier opinion, in 1924 he referred to the people of India as ‘one of the most cultured races within the Empire’, and called for the enfranchisement of all Indians resident in Australia according to the resolution of the Imperial Conference of 1921. The next year, when 2000 Indians resident in Australia were given the vote, he supported the legislation ‘from a British, an Australian, and a democratic point of view’. Reid visited India in 1925, and was convinced that Australia could and should support a much larger population. He claimed that ‘India could carry its own population comfortably, and provide its people with all the necessaries of life, but for the misgovernment that has arisen through British interference’.[9]

The exigencies of World War I completed Reid’s political and ideological metamorphosis. By February 1917 he had become a prominent organiser for the pro-conscription cause and, with the backing of Hughes, was given a place on the Nationalist’s Queensland Senate ticket. His former opponents transformed the old labour agitator into a ‘Democrat of the old, moderate school’, who had ‘now emerged from a well-earned retirement from Purely Patriotic motives’. The Worker noted sarcastically: ‘After reading that praise from the Liberals “Rat” Mat must have fairly burned with pleasure’. Reid explained his new allegiances by saying that ‘the world was turning upside down, and more or less all parties were turning with it’ and that to ‘stick to any party under present conditions seemed a stupid policy, and behind the times.’ He urged electors ‘to return a strong National Party in the interests of democracy’.[10]

Reid was successful in his 1917 bid to enter the Senate, and was re-elected in 1922 and 1928. He was appointed to three committees, including the Joint Standing Committee on Public Works, on which he served for eight years. He also chaired the 1921 Royal Commission on the Cockatoo Island Dockyard. Although he still claimed to support the labour movement, the radical of old was gone. The uncompromising and dogmatic idealist had become a pragmatic politician. He was not ashamed of having been a ‘red-ragger’, but said that ‘experience and common sense’ had taught him that a lot of things he had once advocated were ‘empty fads’. He showed some bitterness towards the leading spirits of the Labor Party, whom he saw as undeservedly reaping the benefit of the struggles of himself and other pioneers, and in his early days in the Senate harboured a special enmity for the anti-conscriptionist Labor Premier of Queensland, T. J. Ryan, ‘that great Labour demagogue’.[11]

Reid attributed many of Australia’s economic worries after World War I to the fact that ‘in almost every branch of industry’ there was not a fair return on wages. In 1919 he accused striking unionists of attempting to destroy the arbitration system, thereby undermining the rule of law. The detrimental effects of labour militancy remained an abiding concern. With the onset of the Depression, Reid began to question Australia’s tariff policy, expressing doubt ‘that the protective policy of the Commonwealth has benefited this country as much as we thought it would’. He urged that government ‘look to private enterprise for the solution of many of the problems’ that beset the nation. He was conscious of the growing influence of communism, accusing the Scullin Government of being soft on extremists who were ‘white-anting’ the unions, and the communists of ‘preaching class-hatred of the worst kind’.[12]

In mid-1934 Reid announced his decision not to contest the 1935 election and departed the Senate at the expiration of his term. He lived out the remainder of his life in the Brisbane suburb of Toowong, where he died on 28 August 1947. He was the last of the pioneers of the labour movement in Queensland. Two daughters, Edith Florence and Gertrude Mary, and a son, Arthur, survived him. Despite his apostasy, the Worker was generous to the memory of one who had spent his early years as ‘a vigorous and fearless fighter for the cause’. Among Reid’s bequests was one that enabled the Brisbane lodge of theosophists to renovate their building, Besant House.[13]

[1] D. J. Murphy, R. B. Joyce and Colin A. Hughes (eds), Prelude to Power: The Rise of the Labour Party in Queensland, 1885–1915, Jacaranda Press, Milton, Qld, 1970, pp. 224-5; Rodney Sullivan, ‘Reid, Matthew’, ADB, vol. 11.

[2] Daily Mail (Brisb.), Feb. 1926, p. 8; Brisbane Courier, 25 Mar. 1896, p. 4.

[3] QPD, 28 June 1893, pp. 141-2, 12 Oct. 1893, pp. 1080-1, 14 Aug. 1894, pp. 247-8, 21 Aug. 1901, pp. 444-5, 7 Aug. 1895, pp. 519-20, 23 Aug. 1894, pp. 334-8, 31 Aug. 1894, pp. 408-12, 7 Sept. 1894, pp. 503-5, 11 Sept. 1894, pp. 522-8; Brisbane Courier, 16 May 1895, p. 7; QPD, 15 Aug. 1895, pp. 578-80.

[4] Brisbane Courier, 31 Jan. 1898, p. 6; QPD, 12 July 1893, p. 212, 4 July 1895, pp. 147-9, 2 Aug. 1893, p. 329, 24 July 1894, pp. 87-8; D. J. Murphy (ed.), Labor in Politics: The State Labor Parties in Australia 1880–1920, UQP, St Lucia, Qld, 1975, p. 165.

[5] Murphy, Joyce and Hughes, Prelude to Power, pp. 224–34.

[6] Murphy, Labor in Politics, pp. 173, 176; P. Loveday, A. W. Martin and R. S. Parker (eds), The Emergence of the Australian Party System, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1977, p. 155; Capricornian (Rockhampton), 4 May 1907, p. 41; Murphy, Joyce and Hughes, Prelude to Power, pp. 232-3.

[7] QPD, 13 Aug. 1901, pp. 321-2, 21 Aug. 1901, p. 440; Murphy, Joyce and Hughes, Prelude to Power, p. 230.

[8] ‘Profile of a Theosophist’, Theosophy in Australia, Mar. 1996, pp. 19-20; Jill Roe, Beyond Belief: Theosophy in Australia, 1879–1939, NSWUP, Kensington, NSW, 1986, pp. 152, 216, 266, 279, 302.

[9] CPD, 20 July 1922, pp. 632-6, 638, 2 Apr. 1924, p. 199, 3 July 1925, pp. 690–1, 15 July 1926, pp. 4165-9.

[10] D. J. Murphy, T. J. Ryan: A Political Biography, UQP, St Lucia, Qld, 1990, p. 228; Brisbane Courier, 23 Mar. 1917, p. 6, 3 Apr. 1917, p. 7; National Leader (Brisb.), 20 Apr. 1917; Worker (Brisb.), 3 May 1917, p. 10; Brisbane Courier, 12 Apr. 1917, p. 8.

[11] CPD, 11 July 1923, p. 907, 6 Sept. 1917, p. 1729, 7 Sept. 1917, p. 1820.

[12] CPD, 11 July 1923, p. 906, 9 July 1919, p. 1051, 23 Oct. 1919, p. 13833, 7 June 1933, pp. 2154-6, 21 Oct. 1931, p. 951, 19 Nov. 1931, p. 1780.

[13] Queenslander (Brisb.), 5 July 1934, p. 33; Telegraph (Brisb.), 28 Sept. 1946, p. 3; Courier Mail (Brisb.), 29 Aug. 1947, p. 4; Worker (Brisb.), 1 Sept. 1947, p. 2; ‘Profile of a Theosophist’, Mar. 1996, p. 20.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 2, 1929-1962, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Vic., 2004, pp. 339-343.