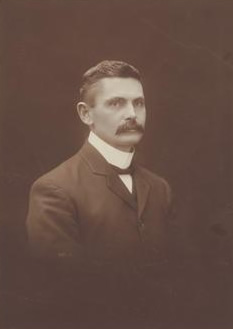

FERRICKS, Myles Aloysius (1875–1932)

Senator for Queensland, 1913–20 (Australian Labor Party)

Myles Aloysius Ferricks was born in Maryborough, Queensland, on 12 November 1875, the fourteenth child of Austin and Mary, née Sheridan. Educated at the Albert State School and Maryborough Christian Brothers, he subsequently passed the Sydney University Junior Examination. With a farm upbringing and a first-class engine driver’s certificate, he was able to turn his hand to a variety of occupations from teaching to railway work. He also mined for gold at Ravenswood, went sugar farming at Proserpine and was a journalist for the Ravenswood Mining Journal and the Bowen Independent. He was an accomplished sportsman, achieving prominence in swimming and rugby football. He played rugby for Rockhampton in notable matches against New South Wales, Mount Morgan and Charters Towers. In 1895, he visited Sydney with a touring Central Queensland rugby team.

Ferricks’ working-class, Irish Catholic background predisposed him to labour politics and ‘Australianism’. (In 1917, he would second a successful Senate resolution in favour of home rule for Ireland.) He was proud of his Irish ancestors in County Mayo whom he ‘traced’as far back as the Spanish Armada. He told how his father had been driven from the land in Ireland by ‘rack-renting land-lords’ and had worked long hours for low pay in industrial England before migrating to Australia. Myles’ inherited sense of historical injustice, and his father’s resentment of working conditions in Britain forged his sympathy for the Australian labour movement. He remembered from his own youth, the bitter sight of ‘the Gatling guns going out west to shoot down the shearers who had presumed to go on strike for better labour conditions’. His leaning towards organised labour was reinforced when he himself endured ‘the trials and struggles that are so often the lot of those earning their bread in humble positions’.[1]

At thirty-three years of age, Myles married, on 12 April 1909, Beatrice Ingham Waugh, in Ayr, North Queensland. There were two daughters, Ellen Mary and Beatrice Eileen. In the same year, Ferricks entered politics—as the Labor Member for Bowen in the Queensland Legislative Assembly. He was in ‘the front rank’ on the labour side when it came to dealing with industrial conflicts such as the sugar strike of 1911 and the Brisbane tramway strike of 1912. But a surge of anti-Labor sentiment in the aftermath of the bitterly fought tramway struggle contributed to his defeat in the 1912 Queensland elections.

In 1913, he was elected as a Queensland senator. In an attack during the campaign on middlemen who were ‘fleecing’ the farmers, Ferricks referred to the Queensland produce agents, Denham Brothers. The firm was associated with the conservative premier, Digby Denham. Denham prosecuted Ferricks for libel. Threatened with bankruptcy and the loss of his Senate seat, Ferricks gained trade union and Labor Party support for an appeal, which in the end did not eventuate as the matter was settled out of court.

Ferricks used his first speech in the Senate to support the ‘new Protection’ and the basic wage. He referred to some conservative senators as no more than delegates of the Employers’ Federation of Australia. He spoke of his dissatisfaction with the number of legal challenges to the High Court’s rulings and bolstered his argument with specific examples of how Commonwealth Conciliation and Arbitration Court awards were evaded by employers. [2]

The Senate provided Ferricks with a forum to air two of his greatest phobias, tipping and Chinese immigration. He argued that the practice of tipping on railways and coastal steamers was anti-democratic and un-Australian. It was, he believed, ‘eating into the heart of the Australian nation’ by subsidising low wages and encouraging servility among working people. Ferricks made the long rail journeys from his Brisbane home to the Senate in Melbourne without the assistance of porters or the early morning cup of tea which tipping ensured.

Ferricks was a fervent supporter of White Australia. He was convinced the policy was being undermined by a Chinese ‘invasion’ of Australia through Darwin, with a subsequent drift of Chinese people from the Northern Territory into Queensland. Here, he contended, encouraged by Queensland’s ‘Tory Government’, they leased land and grew bananas of inferior quality to those imported from Fiji or grown in southern Queensland by white farmers. He complained bitterly of North Queensland’s Chinatowns, whose inhabitants maintained their own culture. He described narrow streets where ‘Chinese may be seen wearing sandals, loose robes, and flying pigtails . . . walking up and down, jeering in their own lingo at white men and women’. Race was a subject which induced a degree of irrationality in Ferricks. In 1915, he was telling the Senate that Chinese in the southern states and North Queensland were ‘obedient and humble’, while those in the Northern Territory were quite the opposite. He claimed that in the Territory, the Chinese taunted volunteer white soldiers over their low pay, and that Chinese children playing with their toy soldiers in the streets of Darwin would call out to these servicemen on their way to war: ‘ “Another blanky white man killed” ’.[3]

Ferricks was sceptical about Australia’s participation in World War I, believing ‘Democracy and war’ were ‘incompatible’. He felt little affinity for Britain or the Empire. Australia and the working class had first claim on his loyalties. He tended to identify deference to Britain with capitalism, because those who control the money market, he said, are the people who sing ‘Rule Britannia’ and ‘God save the King’ three times a day. He regarded the British Foreign Service as an unaccountable ‘exclusive coterie’ staffed by aristocrats, and liable to ‘drag Great Britain and the Empire into war’. He believed World War I was principally ‘a fight for the wealth producers and wealth owners’, who contributed comparatively little towards the costs of the struggle. Indeed a ‘cormorant class of capitalists’ was able to profit unconscionably from investments in war loans, while workers were ‘going into the trenches and fighting to protect wealth’. He welcomed the outbreak of the Russian Revolution in 1917.

Perhaps Ferricks’ most notable contribution as a senator was his prominence in the fight against conscription, which led to the disintegration of W. M. Hughes’ Labor Government and a split in the Labor Party. His anti-conscription speeches in the Senate, in party councils and on public platforms around Australia were eloquent and uncompromising. As early as July 1915, he called for the ‘conscription of wealth’ rather than the ‘conscription of men’. He associated conscription with anti-democratic militarism spiced with class discrimination. He described a common ‘sight for the gods’ in Melbourne’s Collins Street—battle-shy Australian army officers ‘with their gold-headed canes, flicking their gloves’. He did not spare those Labor colleagues who took a different view. He wrongly dismissed Hughes’ visit to Britain in the first half of 1916 as a ‘self-invited trip’. After Hughes’ removal from the Labor Party in November 1916, Ferricks pilloried him for his lack of ‘Australianism’ and betrayal of the labour movement, which had lifted him ‘out of the gutter of oblivion to the highest position in the land’.[4]

Other issues, that engaged his attention in the Senate included the sugar industry and the administration of the Northern Territory. In advocating a greater reward for sugar farmers, Ferricks drew on his own experience as an unsuccessful farmer and his precise knowledge of the industry’s economics. He criticised the privileged market position of the Colonial Sugar Refining Company, but defended the industry’s protected status on the basis of its contribution to the national economy and European settlement of North Queensland. Ferricks’ interest in the Northern Territory was sparked by his fears that its administration was lax on White Australia and overprotective of corporate interests including those of the Vestey Brothers.

Ferricks lost his Senate seat in the 1919 election. He re-entered state politics in 1920 as the Member for South Brisbane and retained his seat in 1923 and 1926. Characteristically, he assumed an oppositionist posture within his own party and trenchantly criticised Labor Premier ‘Ted’ Theodore for his cautious approach to improving the lot of wage earners. (In 1924, Ferricks unsuccessfully challenged Theodore for preselection for the federal seat of Herbert.) Ferricks was defeated in the anti-Labor electoral tide of 1929, when he stood again for South Brisbane. In 1931, he failed to win the federal seat of Maranoa, and was subsequently unsuccessful in gaining pre-selection for the state seat of Merthyr.[5]

The Depression winter of 1932, even in sub tropical Brisbane, was bitter for Myles Ferricks. His attempts to re-enter politics had been rebuffed by his Party colleagues. Moreover, he encountered difficulties in re-establishing himself in a career outside politics. His employment as a commercial traveller for a wine and spirits merchant had ceased and his only job offer was one ‘that any ordinary man out of work would have hesitated before accepting’. Somewhat at a loose end when he encountered one of his few close friends, he appeared also depressed and unusually talkative about his stalled political career and uncertain prospects. Three weeks later, on 20 August 1932, Ferricks died unexpectedly at his Eagle Junction home. His funeral began with a Requiem mass at St Stephen’s Roman Catholic Cathedral. In his panegyric, Archbishop James Duhig, an old acquaintance, acknowledged that ‘Myles Ferricks belonged to the working class’, adding that ‘no sordid or selfish motive ever influenced the views entertained and forcibly expressed by him’. Pall-bearers included the Queensland Premier, William Forgan Smith, and former Prime Minister and Leader of the Federal Labor Party, James Scullin. A mile-long procession conveyed the labour militant’s body to the Nudgee Catholic Cemetery. From the Mareeba branch of the Labor Party in northern Queensland came the tribute: ‘He fought the fight and kept the Faith; no more fitting epitaph is needed’.

C. A. Bernays, historian and Clerk of the Queensland Parliament during Ferricks’ membership, judged him ‘bitter and cynical’. A fellow militant, the somewhat romantic Ernie Lane, remembered Myles Ferricks affectionately as part of a radical ‘rebel fraternity’ who ‘saw in a virile Labour movement the one sound hope of world progress’. A sympathetic contemporary referred to him as a self‑sacrificing ‘splendid character’, who deserved a large share of the credit for saving Australians from the ‘slavery’ of conscription. In 1956, Professor Geoffrey Sawer described Ferricks’ role during the conscription years as representing ‘the most radical Labour point of view in the Senate’. In an unusually confessional address to the Queensland Legislative Assembly in 1925, Ferricks gave a bleak appraisal of his political career, lamenting the frustration of his efforts to re-enter federal politics. He complained of bias toward ‘the first man in Australia to oppose conscription’. His part in the first conscription referendum in October 1916 was his consolation, even ‘self-glorification’, after which he recalled: ‘I did not care . . . if I had died’.[6]

[1] Worker (Brisbane), 24 August 1932, pp. 6, 9; Daily Standard (Brisbane), 24 November 1923, p. 10; Bowen Independent, 23 August 1932; CPD, 8 May 1914, p. 774, 7 March 1917, p. 11052, 23 January 1918, p. 3397, 10 May 1916, p. 7755; Brisbane Courier, 23 August 1932, p. 13.

[2] Worker (Brisbane), 31 August 1932, p. 12; CPD, 27 May 1914, pp. 1479–1480, 8 May 1914, pp. 773-785.

[3] Worker (Brisbane), 31 August 1932, p. 13; CPD, 8 May 1914, pp. 774-779, 29 July 1915, p. 5467.

[4] CPD, 10 May 1916, pp. 7752–7753, 28 July 1915, pp. 5363–5364, 5381-5382, 23 January, 1918, p. 3395, 14 March 1917, p. 11434, 22 May 1916, p. 8209, 9 February 1917, pp. 10388-10389; Stuart Macintyre, The Oxford History of Australia: The Succeeding Age, 1901–1942, vol. 4, OUP, Melbourne, 1986, pp. 162–163.

[5] CPD, 4 November 1915, pp. 7188–7198, 20 August 1919, pp. 11674–11682, 29 July 1915, p. 5466, 17 September 1919, pp. 12356-12357; Ross Fitzgerald, “Red Ted”: The Life of E. G. Theodore, UQP, St Lucia, Qld, 1994, pp. 164–166, 174–177; Morning Bulletin (Rockhampton), 22 August 1932, p. 7.

[6] Daily Standard (Brisbane), 23 August 1932, p. 4; Worker (Brisbane), 24 August 1932, pp. 6, 9; Brisbane Courier, 22 August 1932, p. 11, 23 August 1932, p. 13; Charles Arrowsmith Bernays, Queensland—Our Seventh Political Decade, 1920–1930, A & R, Sydney, 1931, pp. 314–316; E. H. Lane, Dawn to Dusk: Reminiscences of a Rebel, William Brooks, Brisbane, 1939, pp. 114–115; Worker (Brisbane), 31 August 1932, p. 12; Geoffrey Sawer, Australian Federal Politics and Law 1901–1929, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1956, p. 176; QPD, 29 September 1925, pp. 774–775.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 120-124.