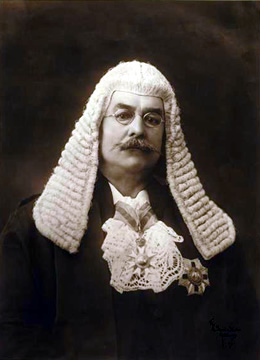

BAKER, Sir Richard Chaffey (1841–1911)

Senator for South Australia, 1901–06 (Free Trade)

Sir Richard Chaffey Baker, barrister, pastoralist and foundation President of the Australian Senate, considered the Senate ‘the pivot on which the whole Federal Constitution revolves’. Baker, the eldest son of twelve children, was born at Adelaide on 22 June 1841 to John Baker, and his wife Isabella, née Allan. John Baker was a pioneer settler who arrived in South Australia in 1839 becoming a successful pastoralist and merchant and later a member of the Legislative Council. He became the colony’s second premier and chief secretary.

Richard Baker was educated at Eton and Trinity College, Cambridge (BA 1864; MA 1871). He was called to the Bar at Lincoln’s Inn in June 1864, and returned home in the same year to set up a legal practice with Charles Fenn of Adelaide. In 1873, he entered into partnership with William Barlow, a distinguished jurist, who became vice-chancellor of Adelaide University. Baker was appointed QC in 1900.

In April 1868, Baker entered politics as the member for Barossa in the South Australian House of Assembly. He was the first native-born South Australian elected to the House of Assembly and, on becoming Attorney-General in J. Hart’s Ministry of 1870–71, the first native-born to become a minister of the Crown. In 1877, following an interval attending to his business interests after the death of his father, he was elected to the Legislative Council. He was Minister of Justice and Eucation (1884–85) and from 1893, President of the Council. From 1869, Baker, first as a private member and then as a minister, attempted to have legislation passed which would make the Auditor-General accountable to the Parliament. When this was achieved, to a considerable extent, by the Audit Act of 1882, he claimed (with some justice) ‘a great deal’ of the credit. While a supporter of Legislative Council reform, Baker was adamant that the Council should be in no way subordinate to the House of Assembly.

As President of the Legislative Council, Baker felt bound ‘to uphold as far and as long as possible a neutral and impartial position’. Nevertheless, he was an active party man, who had been prominent in the formation of the National Defence League (in 1891) which represented conservative, free trade interests in opposition to the United Labor Party and to C. C. Kingston’s Protectionists. The nature of Baker’s relationship with Kingston is illustrated by the famous incident in which Kingston challenged Baker to a duel after a public exchange of insults. Baker waited until the time appointed for the rendezvous and instead of attending himself, alerted the police, who arrested Kingston. A clever defence strategy by his counsel, Josiah Symon saved Kingston from prison or a fine, and he was merely ‘bound over to keep the peace’. Baker remained Kingston’s implacable political enemy, and later helped to prevent Kingston from becoming a member of the influential drafting committee at the 1897–98 federal convention.[1]

As a member of the federal conventions of 1891 and 1897–98, Baker drew on his knowledge of Legislative Council procedure and constitutional law. His publications on Federation included a manual for the guidance of members of the 1891 National Australasian Convention. In Deakin’s opinion he was, in 1891, ‘in advance of all his [South Australian] colleagues in federal knowledge and in the federal spirit’. Baker himself later commented that the convention of 1891 had ‘laid the foundations and built the house of federation’.Baker told the 1898 convention that he had been a keen federalist for years and that it would be ‘one of the proudest moments of my life if I see the great work on which we have been engaged become an actual and realized fact’. Baker was anxious that the Senate should provide an effective mechanism for the consideration and review of legislation, and that it should serve as ‘the sheet-anchor’ of the smaller states. In 1897–98, Baker was a dedicated and skilful Chairman of Committees, presiding over the intricate negotiations and debates on the nearly three hundred amendments to the draft Constitution Bill.[2]

Baker was concerned about the potential power of the executive in a federal system, arguing in his booklet, Federation, that ‘the Senate should be at least as powerful as the House of Representatives’. At the Adelaide convention in March 1897, he said that he was afraid that ‘if we adopt this Cabinet system of Executive it will either kill Federation or Federation will kill it; because we cannot conceal from ourselves that the very fundamental essence of the Cabinet system of Executive is the predominating power of one Chamber’.

At the federal convention of 1891, Baker had moved that the Senate be given equal power with the House of Representatives over all legislation, including the power to initiate and alter money bills, without which it would be ‘a mere dummy’. Baker’s amendment was negatived, twenty-two to sixteen, and a ‘compromise’ was agreed to, allowing the Senate only to request changes to money bills, a notion already suggested in a draft bill prepared by Kingston. This was based on a South Australian precedent—the so-called ‘Compact of 1857’—a term employed by Baker himself. In 1901, Baker wrote that the South Australian ‘compact’ provided that ‘it shall be competent for the Council to suggest any alteration in any such Bill (except that portion of the Appropriation Bill that provides for the ordinary annual expenses of the Government)’.[3]

Sir Richard Baker resigned as President of the South Australian Legislative Council and was elected to the Senate in 1901. At a campaign meeting at Norwood, he responded to the suggestion that the Senate be subordinate to the House of Representatives. ‘That idea’, said Baker, ‘is absolutely destructive of the first principles of the federation . . .’.

At the first sitting of the Senate on 9 May 1901, Baker was elected President of the Senate, securing twenty-one votes in a first-round ballot for the position. Baker was now well placed to play a leading role in the formation of Senate standing orders. Provisional standing orders, draftedby E. G. Blackmore, Clerk of the Senate and Clerk of the Parliaments, in consultation with the Prime Minister, Edmund Barton, had been tabled in the Senate by the Vice-President of the Executive Council, R. E. O’Connor, on 10 May 1901. These orders concluded with a section entitled ‘Joint Standing Orders’, which included requirements relating to the way in which the House of Representatives would respond to the Senate’s requests for amendment of money bills under section 53 of the Constitution. On 21 May, O’Connor, confessing that he had now examined the orders more critically, expressed deep concern about their ‘stringent powers’. He was adamant that the Senate should not be asked to adopt ‘standing orders which are open to so much objection’. He announced that he intended to strike out a number of the orders. Accordingly, when O’Connor tabled his revised draft on 23 May, the offending paragraphs relating to section 53 had disappeared, never to reappear.

When the Senate formed its own standing orders committee on 5 June 1901, Baker, as President, became its chairman. The other committee members were Senators O’Connor, Gould, Downer, Zeal, Dobson, Higgs and Harney, and, once he became Chairman of Committees in late June, Senator Best. On 6 June, the committee recommended, as an interim measure, that the Senate adopt the standing orders of the South Australian House of Assembly. It was felt that these were ‘familiar to the President’ and could be ‘administered by him without difficulty or delay’. On 9 October, after eleven meetings, the committee tabled a report that included the revised standing orders tabled by O’Connor in May. The committee made clear that it had ‘re-arranged the original draft’ by Blackmore and ‘redrafted several of the chapters’, recommending that the Senate ‘agree to the proposed Standing Orders as finally settled’. The general effect of the revisions (especially O’Connor’s deletion) was not only to detach the Senate from House of Commons procedure but to strengthen the Senate against the executive-dominated House of Representatives. The Senate delayed debating the committee’s 1901 draft standing orders until 1903 while continuing to use the South Australian Orders. On 19 August 1903, after two lengthy periods of debate during June and August, the draft orders were agreed to and the Senate standing orders came into operation from 1 September 1903.[4]

Having taken a prominent part in establishing the principle that the Senate ought to have its ‘own practice and procedure’, Baker proposed, in March 1904, a mechanism by which a body of Senate precedent could be built up. Where circumstances arose which were not covered by existing standing orders, the President would suggest the best procedure to adopt. Such decisions—President’s Rulings—would be collected and printed at the beginning of each session of Parliament. ‘By this means’, Baker wrote, ‘ “rules, forms, and practice” supplementary to and explanatory of the Standing Orders would be gradually compiled’. Baker’s suggestion was adopted and the practice has continued. Thus Baker, who was re-elected as President of the Senate on 2 March 1904, created a procedural framework for the Senate, which allowed for flexibility and helped to ensure that the Senate’s independence was maintained. Baker held that the Senate should not import inappropriate procedures from the British House of Commons, thus reinforcing the independence of Senate standing orders and the significance of his own rulings. A notable example of this relates to the allowance, or otherwise, of subject matter in amendments to legislation. In 1904, Baker ruled that the relevance of subject matter as prescribed by Senate standing orders should be the sole test of relevance.[5]

As President of the Senate, Baker shared with the Speaker of the House of Representatives administrative responsibility for the parliamentary departments, and in particular the Department of the Senate. With regard to the latter, he rejected attempts to reduce Senate appropriations, made on the grounds that Senate officers should be paid at a lower rate than their counterparts in the House of Representatives. He dismissed claims that the officials in the upper House had less work than those in the lower House, provocatively concluding: ‘The officers of the Senate should, in my opinion, receive at least the same salaries as those paid to similar officers in the service of the House of Representatives’.

In the Senate chamber, Baker found his own position difficult: ‘In the first place, I have to perform the ordinary duties of a President or a Speaker, and in the second place, under our Constitution, I have to give not a casting vote, but a deliberative vote when, as it sometimes happens, party feeling runs high. The difficulty of reconciling these dual positions is very great . . .’. Nevertheless, Baker often exercised what he termed ‘my right of speaking’. For instance, during debate on the Electoral Bill in 1902, he opposed proportional representation for Senate elections.[6]

For health reasons, Baker left political life at the expiration of his term on 31 December 1906, and retired to his property, ‘Morialta’, Norton Summit, established by his father in 1847. He died there on 18 March 1911, and was survived by two sons, John Richard and Robert Colley, and a daughter, Adelaide Edith. His wife, Katherine Edith, née Colley, whom he had married at St Peter’s Church of England, Glenelg, on 23 December 1865, predeceased him.

Throughout his political career, Baker had remained a successful and highly respected pastoralist. He served as chairman of the Queensland Investment and Land Mortgage Company and was a director of Elder Smith and Company. In 1902, there was an unsuccessful attempt to remove Baker and two other directors of the Wallaroo and Moonta Copper Mining and Smelting Company. This led to a bitter exchange between Baker and Sir Josiah Symon and the subsequent newspaper headline, ‘Senators in Conflict’. Baker was president of the Royal Agricultural Society and the South Australian Jockey Club, and had a long association with the Adelaide Club. In 1895, he was appointed KCMG.

In September 1907, Senator Colonel Neild moved that the Senate record its appreciation of Baker’s ‘distinguished services’ as first President. The Labor leader in the Senate, Gregor McGregor, referred to his long acquaintance with the ex-President, first as an employee, then as a fellow parliamentarian in the South Australian and Commonwealth parliaments.Senator Gould, Baker’s successor as President, stated that senators were honouring not only Baker’s contribution as Senate President, but also his important role in Federation.

Despite close connections with Britain, Baker had remained an Australian patriot. As he told the wife of the governor of South Australia, Lady Tennyson, in 1899: ‘I am not an Englishman, I’m a colonial’, which prompted the lady to confide to her diary: ‘I am so surprised at the way they are so proud of being colonials’.[7]

[1] AFCD, 17 March 1898, p. 2483; Advertiser (Adelaide), 20 March 1911, p. 9; J. J. Pascoe (ed.), History of Adelaide and Vicinity, Hussey & Gillingham, Adelaide, 1901, pp. 241–246; Letter, Sir Richard Baker to Miss Mary Myles, 21 May 1896, Baker Papers, PRG 38, SLSA; Dean Jaensch (ed.), The Flinders History of South Australia: Political History, Wakefield Press, Netley, SA, 1986, vol. 2, pp. 150–152, 370; SAPD, 4 July 1893, p. 164, 25 August 1869, pp. 144–147, 1 September 1869, p. 202, 1 August 1882, pp. 507–508, 19 July 1891, pp. 288–289; Baker Papers, PRG 38, vol. 6, National Defence League of South Australia, SLSA; Rob van den Hoorn, ‘Richard Chaffey Baker: A South Australian Conservative and the Federal Conventions of 1891 and 1897–98’, Journal of the Historical Society of South Australia, no. 7, 1980, pp. 25–26; Adelaide Observer, 31 December 1892, pp. 31–32; Margaret Glass, Charles Cameron Kingston: Federation Father, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1997, pp. 70–77.

[2] AFCD, 23 March 1897, p. 28; In 1897, Baker had published two treatises: Federation, Scrymgour and Sons, Adelaide, and The Executive in a Federation, C. E. Bristow, Adelaide; R. C. Baker, A Manual of Reference to Authorities for the Use of the Members of the National Australasian Convention, W. K. Thomas & Co., Adelaide, 1891; Alfred Deakin,‘And Be One People’: Alfred Deakin’s Federal Story, with an introduction by Stuart Macintyre, MUP, Carlton South, Vic., 1995, p. 38; Register(Adelaide), 1 March 1901, p. 6; AFCD, 17 March 1898, pp. 2483, 2480, 2516–2520; John Quick and Robert Garran, The Annotated Constitution of the Australian Commonwealth, A & R, Sydney, 1901, p. 187.

[3] Baker, Federation, p. 19; AFCD, 23 March 1897, p. 28, 1 April 1891, p. 544, 3 April 1891, pp. 706–707, 6 April 1891, pp. 735, 755; L. F. Crisp, Federation Fathers, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1990, p. 325; Sir R. C. Baker, Notes on the Constitution of South Australia, Hussey & Gillingham, Adelaide, 1901, p. xiii.

[4] Register (Adelaide), 1 March 1901, p. 6; G. S. Reid and Martyn Forrest, Australia’s Commonwealth Parliament 1901–1988, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1989, pp. 134–146; E. G. Blackmore, Standing Orders Relative to Public Business, Department of the Senate, 10 May 1901; CPD, 21 May 1901, p. 36; Standing Orders Relative to Public Business, Department of the Senate, 23 May 1901; CPD, 5 June 1901, pp. 653–657, 13 June 1901, pp. 1069–1070, 20 June 1901, pp. 1337–1338, 28 June 1901, 1778–1783; Senate, Journals, 6 June 1901; CPP, Third report of the standing orders committee, 9 October 1901; CPD, 5 June 1901, p. 687, 10 June 1903, p. 654, 18 June 1903, p. 1073, 12 August 1903, p. 3429, 18 August 1903, p. 3728, 19 August 1903, p. 3847.

[5] CPD, 12 August 1903, p. 3440; CPP, Remarks and suggestions on the standing orders, 9 March 1904; CPP, First report of the standing orders committee, 21 April 1904; Rulings of the President of the Senate, Sir R. C. Baker, from 1903 to 1906, vol. 1, Government Printer, Melbourne, c.1910; Reid and Forrest, Australia’s Commonwealth Parliament, p. 145; CPD, 27 October 1905, pp. 1402–1403; Letter, Sir Richard Baker to Lord Hopetoun, 19 June 1901, The Senate Letter Book 1901—1916, p. 55, Department of the Senate.

[6] CPD, 24 September 1903, p. 5458, 2 March 1904, p. 6, 20 October 1904, p. 5798, 19 March 1902, p. 11007; Reid and Forrest, Australia’s Commonwealth Parliament, p. 104.

[7] Advertiser (Adelaide), 20 March 1911, p. 9; John Playford, ‘Baker, Sir Richard Chaffey’, ADB, vol. 7; Australasian (Melbourne), 2 August 1902, p. 279; CPD, 18 September 1907, pp. 3365–3370; Alexandra Hasluck (ed.), Audrey Tennyson’s Vice-Regal Days, NLA, Canberra, 1978, p. 39; E. J. R. Morgan, The Adelaide Club 1863–1963, Adelaide, 1963, p. 67; Portraits hang in the Adelaide Club, Parliament House, Adelaide, and in Parliament House, Canberra. The chair used by Baker in the Senate chamber is held by the Adelaide Club.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 139-143.