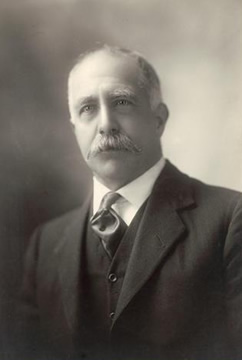

GUY, James (1860–1921)

Senator for Tasmania, 1914–20 (Australian Labor Party)

James Guy’s Protestant theology and his place in a labour movement influenced by Tasmanian social democracy (as opposed to the more radical labourism of the Australian mainland) must be taken into account in assessing the events of his political career. Guy was born in Launceston, Tasmania, on 13 November 1860, the eldest of the twelve children of Andrew, storeman, and Margaret, née Polock. He was educated at various state schools, after which he worked for the blacksmith, W. Gurr and Son, until about 1909.

In 1903, Guy was a co-founder of the Tasmanian Workers’ Political League (a forerunner of the Tasmanian Labor Party) and an influential member of its executive. He would later recall the ‘jeers and sneers’ that greeted the inception of the Party in Tasmania, the opposition of the established press, and the misrepresentation of the Party’s aims by its opponents.

Elected in 1903 as the League’s first treasurer, Guy became president (1904–06, 1908). He was general secretary in 1907 and again from 1909 to 1921, when his son, James Allan, who later became a Liberal, took over the position. In 1917, Guy was again treasurer. Once described cynically by the Launceston Examiner, as a‘shining light’ of the Labor Party, Guy corresponded with the prominent Tasmanian, King O’Malley, MP, on matters which included electoral rolls, the Labor pledge and the central executive’s rules relating to pre-selection. Tasmanian delegate at interstate Labor conferences in 1911, 1915, 1919 and 1921, in May 1918, at an annual conference in Hobart, Guy moved that the League’s name be changed officially to that of the ‘Australian Labor Party’.[1]

In April 1909, Guy was elected to the House of Assembly at the top of the poll for Bass, fell to fourth place in April 1912, and lost his seat nine months later.Guy’s first speech in 1909 stated that his main concern was to alleviate poverty in Tasmania. He supported wages boards, but said also that he wished to provide a better income for Tasmanian members of Parliament. He favoured the abolition of the Legislative Council, holding that with ‘fourteen Chambers and seven Governors to govern less people than were in the City of London’ Australia was over-governed.[2]

Guy stood unsuccessfully for the Senate in 1906, when, hopeful of Labor’s future prospects in Tasmania (where it had not yet won government), he was convinced that a cautious policy of ‘sweet reasonableness’ would succeed. After a second defeat in 1913, Guy went on to win a Senate seat in the 1914 federal election (following the double dissolution), serving one term. He announced to fellow senators that his principle in debate would be one of toleration of his colleagues’ arguments and views. ‘I shall not seek to offend anybody purposely’, he said, a noble aim which in the end he did not achieve. He affirmed his belief in the Labor Party, which he considered ‘destined to bring about better conditions for the great mass of the people than they have ever enjoyed before’. Like other Tasmanian senators, he was particularly keen to protect what was seen as Tasmania’s vulnerable position in the new Federation, and determined to publicise difficulties that Tasmania, the poorest of the states, had in coping with the problems of geography, isolation and a small population.

Guy was a supporter of the Commonwealth Bank, describing the measure authorising its establishment as ‘the greatest piece of legislation ever enacted in the world’s history’. However, he spoke mostly on questions relating to social welfare. A constant theme was the need to improve the living conditions of the less well-off. He sought to gain recognition of the principle that widows with children should be granted a pension. He hoped that Australian society would eventually reach the position where ‘every child born into this community will have the amplest opportunity to live the full and free life that is the right of every human being’. He spoke of the hardship facing many Tasmanian families, calling attention to the high price of meat, which made its purchase beyond the reach of many, or to the miserable existence of ‘a poor woman left with little children, the breadwinner being gone’. He opposed the payment of a pension to the Chief Justice of the High Court, Sir Samuel Griffith, on the grounds that the Chief Justice should have no claim to a benefit above that of the most humble of public servants (who had no pension).[3]

The events of World War I were troubling to this pious man, who regarded war as ‘the most deadly sin’. He criticised the ‘faked’ news, the suppression of information and the failure to trust the people with the unvarnished truth. He refused to subscribe to the view that the progress of a nation depended on the fighting qualities of its soldiers: ‘I abhor that school of thought which glories in war, and which affirms that the more war-like nations are the greatest nations’.[4] Although he had expressed support for the war effort during the 1914 election campaign, Guy was firmly in the anti-conscription camp, describing overseas compulsory military service in 1916 as ‘iniquitous, oppressive, hateful, and repulsive’. The following January, at the Tasmanian State Labor Conference, Guy sought unsuccessfully to have conscription ‘anywhere, everywhere, and under any circumstances’ declared to be wrong.[5]

Guy’s Senate career is most remembered for his absence from the Senate on a memorable occasion in February 1917, when the Hughes Government attempted to extend the life of the Parliament until the end of the war. For this purpose, Prime Minister Hughes needed to ‘adjust’ the Senate numbers, and several Tasmanian Labor senators were seen as vulnerable to pressure. Guy was one. Very suddenly, Guy found himself unable to leave his bed in Struan Hospital in Launceston. The simultaneous absence of Senator Long and the resignation from the Senate of Rudolph Ready led to the conclusion that Guy was obligingly fitting in with the Prime Minister’s scheme. Guy emphatically denied this. It has never been clear whether his illness was genuine or not.[6]

In poor health during his final campaign, Guy was defeated at the 1919 election and died on 23 August 1921 at his home in Inveresk, Launceston, not far from his birthplace, his occupation still that of a blacksmith. A tireless supporter of his Church, Guy worked as manager and trustee of the Chalmers Presbyterian Church and taught in its Sunday school. He was a director of the Permanent Building Society and, through his involvement in friendly society work, was chairman of the Launceston United Friendly Societies’ Dispensary. A temperance advocate, Guy was also secretary of the Independent Order of Rechabites. During World War I, he had been a member of a Senate select committee which inquired into the effect of liquor on the Australian soldiery. In a dissenting report, he had recommended that the Government ‘should prohibit the importation, manufacture, and sale of wines, beer, and spirituous liquors throughout the Commonwealth’.[7]

On 13 November 1884 at Launceston, he had married, in accordance with the rites of the Presbyterian Church, Margaret McElwee (whose brother George was later a member of the Tasmanian Legislative Council). His wife and family (a daughter and four sons) survived him. Guy was described by George Pearce as a ‘lovable character’.[8]

[1] CPD, 8 October 1914, p. 16; Richard Davis, Eighty Years’ Labor: The ALP in Tasmania, 1903–1983, Sassafras Books and University of Tasmania, Hobart, 1983, pp. 4–5, 117–120; Mercury (Hobart), 5 June 1903, p. 2, 6 June 1903, p. 2, 8 June 1903, p. 5; Examiner (Launceston), 24 August 1921, p. 6; Lloyd Robson, A History of Tasmania: Volume II, Colony and State from 1856 to the 1980s, OUP, Melbourne, 1991, pp. 218–220; D. J. Murphy (ed.), Labor in Politics: The State Labor Parties in Australia 1880–1920, UQP, St Lucia, Qld, 1975, p. 436; Examiner (Launceston), 24 April 1909, p. 6; Mercury (Hobart), 5 June 1903, p. 2, 6 June 1903, p. 2, 8 June 1903, p. 5; Patrick Weller (ed.), Caucus Minutes 1901–1949: Minutes of the Meetings of the Federal Parliamentary Labor Party, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1975, vol. 1, p. 197; Patrick Weller and Beverley Lloyd (eds), Federal Executive Minutes, 1915–1955: Minutes of the Meetings of the Federal Executive of the Australian Labor Party, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1978, p. 24; O’Malley Papers, MS 460/3304, 3583, 3524, 3522, NLA; Daily Post (Hobart), 11 May 1918, p. 8.

[2] Mercury (Hobart), 6 April 1909, p. 6; 6 May 1909, p. 5, 2 July 1909, p. 7, 8 July 1909, p. 6.

[3] Murphy, Labor in Politics, p. 412; CPD, 8 October 1914, pp. 14–21, 22 April 1915, p. 2524, 14 June 1918, pp. 6057–6058, 20 December 1918, pp. 9898–9900.

[4] CPD, 13 July 1917, pp. 177–178, 14 June 1918, p. 6057.

[5] Examiner (Launceston), 3 September 1914, p. 3; CPD, 22 September 1916, p. 8882; Daily Post (Hobart), 11 January 1917, p. 7, 12 January 1917, p. 3.

[6] Geoffrey Sawer, Australian Federal Politics and Law 1901–1929, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1956, pp. 130–131; L. F. Fitzhardinge, The Little Digger 1914–1952: William Morris Hughes: A Political Biography, vol. 2, A & R, Sydney, 1979, pp. 257–258; Ernest Scott, Australia During the War, A & R, Sydney, 1943, pp. 382–383; CPD, 18 July 1917, pp. 197–198; Daily Post (Hobart), 3 March 1917, p. 6.

[7] CPP, Report of the select committee on the effects of intoxicating liquor on Australian soldiers, 1918.

[8] CPD, 26 August 1921, p. 11343; Examiner (Launceston), 24 August 1921, p. 6.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 257-259.