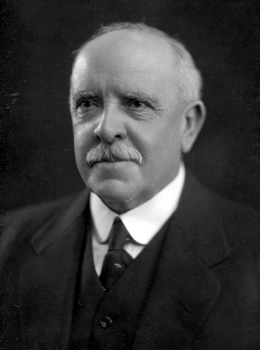

KINGSMILL, Sir Walter (1864–1935)

Senator for Western Australia, 1923–35 (Nationalist Party; United Australia Party)

In October 1897 Kingsmill was elected to the Western Australian Legislative Assembly seat of Pilbara. Known among the miners he represented as ‘Kingey’, he was initially a supporter of Premier John Forrest. An advocate of Federation, he hoped that the combined efforts of the people’s representatives in each colony would ‘quickly result in a United Australia, free from those vexatious heart-burnings and petty jealousies which arise from the presence of imaginary boundaries between peoples’. In 1899 he was made Opposition Whip. He took a keen interest in the electoral provisions for Western Australia’s 1899 referendum on Federation, especially in relation to the availability of electoral rolls in remote areas of the state. He recollected that at one place ‘in his own constituency they were going to have a miners’ institute, but had to “swap” it away for a lock-up’. Earlier in 1899, Kingsmill voted against women’s suffrage as ‘not urgent’, as it doubled the power of the metropolitan vote.

After the 1901 election, Kingsmill became Minister for Works in the Liberal ministry of Premier George Leake and Commissioner of Railways in Leake’s second ministry. When Leake died in June 1902, Kingsmill served for a short time as acting premier. Resigning from the Assembly, in 1903 he won a seat for the Metropolitan–Suburban Province in the Legislative Council, where he became Leader of the Government (1903–04). In the James Ministry, Kingsmill was Colonial Secretary and Minister for Education (1902–04), holding the same positions in the Rason Ministry (1905–06). In March 1910 he resigned from the Council to make an unsuccessful bid for the Senate, and in May was re-elected to the Council. From 1906 to 1919 he was Chairman of Committees. In August 1919 he became President of the Legislative Council, holding the position until his defeat in May 1922. Throughout his long service in the Western Australian Parliament he was an advocate of parliamentary committees, serving on thirty-two select committees.[2]

Kingsmill, representing the Nationalist Party, stood again for the Senate and was elected at the federal election in December 1922. He started his first speech in July 1923 by stating that he and the Labor Leader of the Opposition in the Senate, Senator Gardiner, whom he considered ‘a veritable Robinson Crusoe of politics’, held similar views in regard to the role of the Senate. Regretting the extent of ‘party spirit’, Kingsmill wondered why ‘the principal officers of Parliament’ (presumably the President and Speaker) were elected on party lines, and said his wish was ‘to carry out the intention of the Constitution’, leaving the states in control of their own affairs.

Despite deploring party politics in the Senate, Kingsmill himself, who spoke well, and not infrequently, generally upheld the policies of his own party, though he was somewhat less vehement on states’ rights than most Western Australian senators of the time. Indicating a particular interest in national development and finance, he became a member of the influential Public Accounts Committee from October 1924 to August 1929, serving as vice-chairman from July 1926 and as chairman from March 1927. From January 1923 to August 1929 he served also as a temporary chairman of committees.[3]

On 14 August 1929 Kingsmill was unanimously elected President of the Senate. According to the press, the Government party room vote, held on the previous evening, had not been so smooth. The vote had been tied between Kingsmill and Senator Lynch, with the selection finally made by the casting vote of the Leader of the Government in the Senate, George Pearce. Proud of his position as a parliamentarian, Kingsmill had once posed the question: ‘Is there any career which should demand a higher type of intellect and character than a parliamentary career?’ He was emphatic that a member’s work ‘does not begin and end’ in the chamber. Support for higher salaries for politicians was based on the view that it provided a wider choice of candidates and helped to ensure that the politics and government of the country were not looked upon as ‘one of the recreations of the idle rich’. According to Kingsmill’s dictum ‘we cannot pay too much for good government’.

As President of the Senate, Kingsmill, loyal to the wearing of wig and gown, was strict in the maintenance of standing orders and keen to ensure decorum. One of his most vocal opponents, Labor’s Senator Dunn, even described him as ‘the Mussolini of the Senate’. Kingsmill tried to prevent the reading of parliamentary speeches, and took exception to references to the ‘other place’. Phrases and terms that were forbidden in debate included: ‘dirty attack’, ‘dirty lies’, ‘humbug’, ‘twaddle’, ‘rot’ and ‘buckshee’. The latter word had been often used to depict what is today colloquially described as a ‘junket’. Although Kingsmill once claimed that the ‘natural line of cleavage’ between parties was based on economy, he demanded an apology when it was asserted that some ‘honorable senators’ were representing the ‘money-bags’ of Australian capital. Nevertheless, his ideological position was clear when he contended that it was indisputable that a man working for himself was a better citizen than one working for wages.

When, in May 1930, Dunn brought to the attention of the Senate the secessionist movement in Western Australia, Kingsmill ruled that the matter was ‘at present outside any phase of federal politics’. Another ruling related to formal conferences between the two houses. Only two of these conferences have occurred in the history of the Commonwealth, both during Kingsmill’s presidency, when he ruled that senators could not be compelled to be members of conferences, and that there was nothing in the standing orders to prevent the Senate adjourning during a conference. When, shortly after J. T. Lang’s dismissal as Premier of New South Wales by the state Governor, Sir Philip Game, Senator Dunn ostentatiously placed on his desk in the Senate chamber a bust of the aforesaid Lang, Kingsmill ruled that senators may not have on their desks items objectionable to other senators. On 30 August 1932, at a meeting in Canberra of United Australia Party senators, Kingsmill narrowly lost his party’s support for the presidency to Senator Lynch. This meant that when the Senate met later in the day Kingsmill was defeated. In the following January he was awarded a KB.[4]

In 1933, when J. T. Pinner, a Commonwealth Public Service Board inspector, submitted a report on the parliamentary departments that proposed merging the five departments as a cost-saving measure, Kingsmill, who had been responsible for Pinner’s appointment, responded by pointing out the fundamental differences between Parliament and the executive: ‘A great deal of the trouble that has arisen . . . has been due to the executive placing . . . the administration of Parliament on the same basis as that of the Public Service’.[5]

In both state and Commonwealth parliaments Kingsmill advocated improvements in railways, postal services and telecommunications. He supported scientific research to foster the development of resources and was also something of an environmentalist. He took a keen interest in trade. In the Western Australian Parliament, after World War I, he had conducted a select committee inquiry on the prospects of improved trade with South-East Asia, but no steps were taken to comply with his recommendation for the appointment of trade commissioners. In the Senate he strongly supported the 1932 United Kingdom and Australia Trade Agreement Bill. He had reservations about the impact of the tariff on Western Australia but he valued the fact that a start had been made ‘towards binding the Empire together’.[6]

Prepared to take an individual stance on the big issues, Kingsmill deplored the practice of labelling all anti-conscriptionists in World War I as unpatriotic. Later, when out of sympathy with his party’s clamour for secession, he lost preselection for the 1934 elections. His residence in Sydney from the time of his Senate election may have led to his losing touch with the ‘grass roots’. He died on 15 January 1935 at his Elizabeth Bay home, and was cremated with Anglican rites, following a state funeral. On 20 December 1899, he had married Mary Agatha Fanning at St Patrick’s Catholic Church in Fremantle. Mary survived him but they had no children. After such a long parliamentary career, perhaps it was fitting that he died in office.[7]

[1] G. C. Bolton, ‘Kingsmill, Sir Walter’, ADB, vol. 9; W. B. Kimberly (comp.), History of West Australia: A Narrative of Her Past Together with Biographies of Her Leading Men, F. W. Niven & Co., Vic., 1908, p. 200; J. S. Battye (ed.), The Cyclopedia of Western Australia, vol. 1, Hussey & Gillingham, Adelaide, 1912, p. 328; Twentieth Century Impressions of Western Australia, P. W. H. Thiel, Perth, 1901, p. 33; West Australian (Perth), 16 Jan. 1935, p. 16; Kingsmill Papers, MS 745, NLA; Harry C. J. Phillips, Tennis West: A History of the Western Australian Lawn Tennis Association from the 1890s to the 1990s, Playright Publishing, Caringbah, NSW, 1995, pp. 75, 80, 84, 87, 88, 101; The editor is indebted to the marketing manager, Tennis West, Perth, and Steve Howell, Battye Library, LISWA; CPD, 11 June 1926, p. 2963; British Australasian (Lond.), 14 June 1917, p. 17; SMH, 5 Apr. 1939, p. 14

[2] Daily News (Perth), 13 Aug. 1934, p. 4; WAPD, 17 Aug. 1897, pp. 8–10, 6 June 1900, p. 274, 24 Aug. 1898, p. 1203; David Black (ed.), The House on the Hill: A History of the Parliament of Western Australia 1832–1990, Parliament of Western Australia, Perth, 1991, pp. 83, 437, 448–9; SMH, 1 Aug. 1919, p. 7.

[3] CPD, 12 July 1923, pp. 988–96.

[4] CPD, 14 Aug. 1929, p. 1; SMH, 15 Aug. 1929, pp. 11, 12; WAPD, 5 Sept. 1918, p. 176, 24 Nov. 1897, p. 556; Gavin Souter, Acts of Parliament, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1988, p. 262; CPD, 13 Nov. 1931, p. 1650, 10 June 1931, p. 2599, 9 July 1930, p. 3860, 7 Aug. 1930, p. 3519, 24 July 1930, p. 4556, 26 Feb. 1932, p. 401, 19 Nov. 1931, p. 1813; WAPD, 5 Sept. 1918, p. 175; CPD, 2 May 1930, p. 1393, 23 Nov. 1932, pp. 2666–7, 28 May 1930, pp. 2191–2, 29 May 1930, pp. 2278–80; Harry Evans (ed.), Odgers’ Australian Senate Practice, 10th edn, Department of the Senate, Canberra, 2001, pp. 78, 79, 139, 144, 165; CPD, 31 Aug. 1932, p. 3; Argus (Melb.), 1 Sept. 1932, p. 9; SMH, 2 Jan. 1933, p. 6.

[5] G. S. Reid and Martyn Forrest, Australia’s Commonwealth Parliament 1901–1988, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1989, pp. 414, 427–8; CPD, 27 June 1933, pp. 2624–7.

[6] WAPD, 12 Aug. 1902, pp. 465–74, 8 July 1914, p. 221; CPD, 17 Aug. 1923, pp. 2950–1, 27 June 1924, p. 1682, 6 Aug. 1924, pp. 2838–9, 12 July 1923, pp. 991–2, 26 June 1925, p. 484, 11 June 1926, pp. 2960–6, 2 Dec. 1927, pp. 2480–3, 5 Dec. 1933, pp. 5471–2; WAPD, 5 Sept. 1918, pp. 178–9; WAPP, Report by Senator the Honorable W. Kingsmill on the Possibilities of Opening up Trade with Federated Malay States and Java, 1919; CPD, 23 Nov. 1932, pp. 2663–9.

[7] CPD, 28 May 1930, p. 2192, 13 Mar. 1935, p. 4; SMH, 20 July 1934, p. 12; Advertiser (Adel.), 16 Jan. 1935, p. 18; West Australian (Perth), 16 Jan. 1935, p. 16; SMH, 15 Jan. 1935, p. 12, 16 Jan. 1935, pp. 12, 14, 17 Jan. 1935, p. 6, 18 Jan. 1935, pp. 8, 14, 30 May 1935, p. 10.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 2, 1929-1962, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Vic., 2004, pp. 26-29.