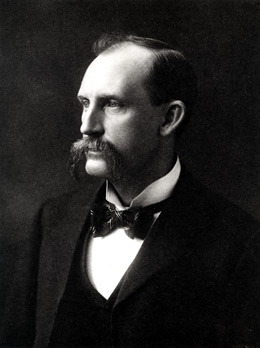

DAWSON, Andrew (Anderson) (1863–1910)

Senator for Queensland, 1901–06 (Labor Party)

‘Andy’ Dawson. The name conjures up a blue flannelled miner or a grease-stained shearer, or a heavy-footed ploughman. Senator Dawson has been all three and more.

Andrew (Anderson) Dawson was born on 16 July 1863, at Rockhampton, Queensland, son of Anderson Dawson, miner, and his wife Jane, née Smith. Shortly after his birth, Dawson’s parents died and he was placed in a Brisbane orphanage until he was nine. Moving to Gympie with an uncle, he attended school until he was twelve. Going on to Charters Towers, he worked as a miner, bullock-driver and newspaper ‘runner’ on Thadeus O’Kane’s radical Northern Miner. By the time he was nineteen, Dawson had achieved a responsible position as ‘amalgamator’ of one of the gold batteries in Charters Towers. In the mid-1880s, he ‘pushed his parcel’ and followed the gold rush to the Kimberley in Western Australia, but failure brought him back to Charters Towers where on 21 December 1887 he married the widow Caroline Ryan, née Quinn.[1]

Dawson was originally attracted to politics by the Irish home rule question and in 1890 emerged as a political pamphleteer when he published The Case Stated, an able plea for the creation of an Australian republic. The pamphlet was freely available inCharters Towers at John Dunsford’s newsagency, a republican stronghold. Throughout 1890, Dawson was closely involved in the running of the Australasian Republican Association (ARA) and in February 1891 was elected the ARA’s second president (the immediate object of the ARA had been to assist in the creation of a third party in Queensland politics). Dawson was also president, and later organiser, of the district council of the Australian Labour Federation (ALF). During the Queensland shearers’ strike, he was appointed chairman of the Queensland provincial council of the ALF, and was public in his support of socialism.

During 1891 and 1892, Dawson had a partnership in a ‘general and produce’ store with John William Ward, a fellow republican and unionist, and a third party called Watson. The partnership was dissolved in June 1892 when Dawson ran as an endorsed Labor candidate for the Dalrymple divisional board in order to test Labor’s voting strength. Dawson topped the poll in the town ward and as a result was boycotted by the anti-home rule faction for two years so ‘that he had to pick mullock heaps to get a living’.[2]

Like many unionists interested in politics, Dawson used the press as a forum for disseminating his political ideas. During 1892, he wrote for the Northern Miner (edited by Thadeus O’Kane’s son, John) and on 18 February 1893 became the first editor of the radical Charters Towers Eagle, a Labor journal which he owned until 1900 with John Dunsford.

At the 1893 Queensland election, at which Labor set out for the first time to win government, Dawson was elected as one of two members for Charters Towers. Dawson gained what was, up to that time, the record number of votes recorded for Charters Towers for any one candidate. In the Queensland Parliament, Dawson spoke on matters affecting mining and railways. He also served as a member of the 1896 royal commission on mining. Dawson strongly objected to Queensland sending a military contingent to the Boer War. He successfully protested against the draft University Bill, which provided that only males could be senators. At the 1896 election, at which Dawson had been returned with an increased majority, Dawson and William Kidston (a Rockhampton bookseller), emerged as leaders of the Parliamentary Labor Party, and in 1899 Dawson was elected leader.

Following the resignation of the Liberal Government in November 1899, Dawson formed the world’s first Labor ministry. This was the ‘Dawson fiasco’, celebrated in Labor mythology as the first Labor Government in the world. In more realistic terms, it was a six-day ministry, which survived only four hours on the floor of the Legislative Assembly, and which resigned on 7 December 1899. Dawson had not expected his government to last long, but had hoped to demonstrate Labor’s desire to take office, and its capacity to administer the state as responsibly as any conservative ministry. Continuing ill health forced him to retire as parliamentary leader of the Labor Party in August 1900.[3]

A staunch supporter of Federation, in 1901 he was a successful candidate for the new Senate. The Worker described him about this time as ‘long in limb, narrow in girth, with a strong inclination to baldness’, and as ‘good-tempered and exceptionally good hearted’. He was viewed as a politician of great promise—‘an able, consistent, and considerate debater, a progressive thinker, and a generous rival’.

Two days before the opening of the Parliament in Melbourne, nine of the twenty-four elected Labor members met under the chairmanship of Dawson to discuss the formation of the Federal Parliamentary Labor Party. This culminated on 8 May in the creation of the Labor Caucus.[4]

At the Senate’s first sitting, Dawson proposed, without success, that the election of the President of the Senate should not be by secret ballot: ‘If honorable members who have been honoured by the people of Australia by being selected to represent them in the Senate are ashamed to cast their votes openly let them say so . . .’. In his speech during the Address-in-Reply, Dawson spoke as ‘an old miner’ on the adverse effect of protection on the development of the gold fields in Queensland. He thought it would be better if mining machinery came into Queensland ‘absolutely free’, while understanding why it was that his colleague, Senator W. G. Higgs from Fortitude Valley, ‘where they make a few pots and saucepans’ was a protectionist. Dawson was later to concede that ‘once a little bandy-legged infant industry had grown up, perhaps it would be better if the crutches of protection were to be thrown aside and burnt’. He also insisted that the tariff be regarded as a ‘non-party matter’ and rejected suggestions by fellow Labor senators, such as Higgs, that the question of ‘Inter-State free-trade and protection against the world’ had influenced Queenslanders’ approach to the first Parliament. Dawson was in favour of a citizen soldiery and school cadet training for boys and girls. On the ‘new woman’, he said that she would be able to assert ‘womanly rights’ that the ‘old woman’ had never been able to assert. Though a strong supporter of a White Australia, he argued that once immigrants had been accepted into Australia they should be accorded ‘at the first possible moment . . . the full rights and privileges of citizenship’.

By August 1902, Dawson had become less than enamoured of federal politics. He was still unwell, and out of pocket, and had ‘had about as much of Melbourne’ as he wanted. The Queensland people, he said, during a debate on the federal capital site, ‘have an absolute unutterable disgust for Melbourne’. He declared that ‘if . . . the seventh circle of Dante’s Inferno were chosen, I should prefer it to Melbourne’.[5]

When Deakin resigned as Prime Minister in April 1904 and Watson formed the first federal Labor Government, Dawson became Minister for Defence—from 27 April to 17 August 1904. Previously, he had called for an inquiry into the circumstances surrounding the retrenchment of a certain Major Carroll. Now, he was instrumental in forwarding the establishment of a select committee into the affair. This foreshadowed a conflict between Dawson and Major-General Hutton (appointed in 1901 to command and organise the Australian land forces) that was to continue throughout Dawson’s ministry.

During a debate on defence regulations in 1904, Dawson was concerned with the conflict of interest for members of Parliament who were also officers on the active list and thus subservient to Hutton. The year before, he had stated that he considered the defence department ‘a very autocratic system, which has gone a long way towards disintegrating the whole force’. Now he referred to several items in a report by Hutton, which he thought not ‘quite proper’. Upon leaving the Ministry, Dawson wrote to the secretary of the defence department thanking him and his colleagues for their services. Dawson made it clear that he and Hutton had not been ‘in touch or in sympathy’. This prompted Hutton to state that ‘if our relations were not of a cordial character the blame does not rest with me’. Afterwards, Dawson considered a high point of his time as minister was that he ‘had pulled down from his pedestal the biggest bounder that had ever commanded the forces in Australia, Major-General Hutton’. Dawson’s later concern with military affairs touched again on the underlying issue of accountability that was at the base of his disagreement with Hutton. In October 1906, he questioned the then Minister for defence, Senator Playford on his authority to make individual defence compensation payments without the consent of Parliament.[6]

Dawson’s support for judicious Liberal–Labor alliances and his unwillingness to pay a £50 election levy placed on Queensland Labor senators caused him to lose favour with the extra-parliamentary leaders of the Party in Queensland. In the selection of Senate candidates by the central political executive in 1906, Dawson finished fourth and was not able to stand. Reservations expressed in Labor circles, however, resulted in a second meeting for preselection at which he was placed third on the ticket. Although Dawson at first withdrew his candidature, he later changed his mind, but it was too late. Dawson filed a writ against the Worker in November 1906 claiming £5000 damages for alleged defamation, then ran as an Independent. He split the Labor vote, finished last, and caused the defeat of Senator Higgs and the other two Labor candidates.

After the election, Dawson followed various occupations in Brisbane and Melbourne. The Northern Miner commented that ‘he was at his best in private life as a raconteur, and that his easy disposition made him always welcome, companionable and popular’. He returned to Brisbane to take part in the 1910 federal elections but fell seriously ill and died on 20 July 1910 in the Brisbane General Hospital. The Government made all the arrangements for the funeral, and the QueenslandParliament adjourned to allow for attendance by its members. His wife, two daughters, Hanorah and Jean, and two sons, Ernest and Robert Leslie, survived him. Dawson was buried in Toowong Cemetery, Brisbane.

In 1910, the Northern Miner wrote: ‘Unquestionably had his physique and other drawbacks not prevented him from holding his place, he would certainly have been Prime Minister of the Commonwealth to-day’. Dawson’s principal drawback was undoubtedly his problem with alcohol.

Nevertheless, for almost ninety years, his name has been part of Labor hagiography as the ‘first Labour premier in the world’.[7]

[1] Punch (Melbourne), 7 July 1904, p. 4; Alcazar Press (comp.), Queensland 1900, Wendt, Brisbane, 1900, p. 146; Charles Arrowsmith Bernays, Queensland Politics During Sixty (1859–1919) Years, A. J. Cumming, Brisbane, 1919, p. 201; D. J. Murphy, ‘The Dawson Government in Queensland, the First Labour Government in the World’, Labour History, no. 20, May 1971, p. 6.

[2] Glenn A. Davies, ‘Atheistical and Blasphemous Notoriety Seekers? The Australasian Republican Association, Charters Towers, 1890–1891’, Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland, vol. 14, August 1990, pp. 99–113; Glenn A. Davies, ‘The Western Republicans: The General Election of 1893’, Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland, vol. 15, November 1994, pp. 440–455; QPD, 19 September 1900, p. 887; Worker (Brisbane), 2 March 1901, p. 9.

[3] D. J. Murphy, R. B. Joyce and Colin A. Hughes (eds), Prelude to Power: the Rise of the Labour Party in Queensland 1885–1915, Jacaranda Press, Milton, Qld, 1970, pp. 74–75; QPD, 9 August 1898, p. 166, 8 November 1898, p. 1057; QPP, Report of the royal commission upon the laws relating to mining for gold and other minerals, 1897; QPD, 11 October 1899, pp. 343–344, 27 October 1899, p. 693, 1 November 1899, pp. 743–744; Ronald Lawson, Brisbane in the 1890s: a Study of an Australian Urban Society, UQP, St Lucia, Qld, 1973, p. 127; Alcazar Press, Queensland 1900; D. J. Murphy and R. B. Joyce (eds), Queensland Political Portraits 1859–1952, UQP, St Lucia, Qld, 1978, p. 212.

[4] Review of Reviews (Melbourne), 20 May 1904, pp. 477–478; Murphy et al., Prelude to Power, p. 238; CPD, 2 July 1903, p. 1708; Worker (Brisbane), 2 March 1901, p. 9; Patrick Weller (ed.), Caucus Minutes 1901–1949: Minutes of the Meetings of the Federal Parliamentary Labor Party, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1975, vol. 1, pp. 43–44; L. F. Crisp, The Australian Federal Labour Party 1901–1951, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1978, p. 111.

[5] CPD, 9 May 1901, pp. 11–14; Gavin Souter, Acts of Parliament, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1988, p. 50; CPD, 30 May 1901, pp. 434, 434–439, 21 May 1902, p. 12720, 2 July 1903, p. 1708, 21 August 1902, p. 15264, 22 September 1903, p. 5246, 20 December 1905, p. 7449.

[6] CPD, 23 September 1903, p. 5329, 2 June 1904, pp. 1842–1844, 26 May 1904, pp. 1591–1592, 2 September 1903, p. 4492, 13 July 1904, p. 3149; Kalgoorlie Miner, 27 August 1904, p. 7; Brisbane Courier, 21 November 1906, p. 5; Major General Hutton to Robert Collins, Secretary, Department of Defence, 25 August 1904, 5954/1, 1185/21, NAA; Senate Journals, 15 September, 12 October 1904; CPD, 12 October 1906, pp. 6484–6485.

[7] Northern Miner (Charters Towers), 21 July 1910, p. 7; Brisbane Courier, 21 July 1910, p. 5; Ross McMullin, The Light on the Hill:The Australian Labor Party 1891–1991, OUP, South Melbourne, Vic., 1991, p. 50; QPD, 20 July 1910, pp. 140, 146.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 81-84.