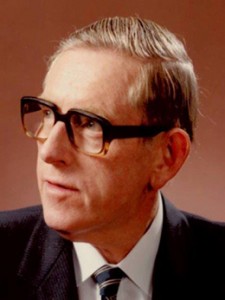

MISSEN, Alan Joseph (1925–1986)

Senator for Victoria, 1974–86 (Liberal Party of Australia)

Alan Missen, law reformer and a champion of civil liberties at home and abroad, was an exemplary parliamentarian whose impact on political life was far out of proportion to his backbench status.

Alan Joseph Missen was born in the Melbourne suburb of Kew on 22 July 1925, the only child of Clifford Athel Missen, a moulder, and (Ethel) Violet Maud Missen, née Bartley. Alan’s early school days at Kew State School were not easy. By his own account, he was a ‘bookworm’ who was not popular and led ‘a lonely sort of life’. However, Missen already possessed an inner toughness and self-confidence which, in the words of his biographer, ‘marked his adult life’. He attended Box Hill High School (1937–41) and won scholarships to Melbourne High School (1942) and the University of Melbourne, where he graduated as a Bachelor of Laws (1946) and Master of Laws (1947), and was placed first in several subjects. Missen was called to the Bar in 1948, but with little work and income his career as a barrister was short-lived. He became a solicitor in the office of Roy Schilling, a leading barrister and briefly a Liberal MLA. From 1953 Missen was a partner in the firm and a senior partner from 1971 until 1980.

Missen joined the Young Nationalists and the United Australia Party while still at school, but his political activity intensified at university, where he became president of the Melbourne University Liberal Club. He joined the Kew branch of the Liberal Party early in 1945, and was especially active in establishing the Young Liberal movement in Victoria. Missen considered himself a ‘progressive radical and not a conservative at all’.

Missen and his close friend, Ivor Greenwood, were members of the successful debating team for the Victorian ‘A’ grade championship of 1959, and in 1963 Missen co-authored The Australian Debater: A Practical Training Guide. It was through debating that Missen met Mary Martha (Mollie) Anchen, a secondary teacher and outstanding debater, whom he married on 4 May 1963. The couple enjoyed an ‘uncanny compatibility’ for the rest of their married life.

In August 1951 Missen, then a vice-president of the Victorian Young Liberals, publicly attacked the Menzies Government’s referendum proposal to ban the Communist Party. Missen believed that any such use of government power ‘must of necessity be a misuse’, ‘a totalitarian power to be given for all time’ and an affront to essential democratic principles of free speech and the presumption of innocence. He was subsequently censured and suspended from his post by the Victorian State Executive of the Liberal Party.

The long-term consequences of his dissent were considerable. Between 1951 and 1968, Missen made six unsuccessful attempts to win Liberal Party preselection for state and federal Parliament; it was twenty-two years before he was able to secure Liberal preselection for any parliamentary contest, although he was a member of the party’s Victorian State Executive for more than a decade. From 1966 he was an influential member of the Victorian Council for Civil Liberties, and participated in campaigns against capital punishment, and censorship.[1]

In August 1973 Missen won second place on the joint Liberal-Country Party Victorian Senate ticket. The calling of a double dissolution by the prime minister, Gough Whitlam, in April 1974, resulted in Missen being pushed down to fifth place. In the election of 18 May he narrowly defeated the DLP’s Senator Frank McManus for the final Victorian seat. Missen was re-elected in 1975, 1977, 1983 and 1984, heading the Coalition ticket in 1977 and the Liberal ticket in 1984.

In one of his earliest speeches to the Senate, Missen reiterated the message he had pursued during his election campaign: ‘there is a great need to pursue the politics of construction rather than the politics of fear in this country … I believe that overwhelmingly it is the duty of honourable senators and members of Parliament to be looking constructively at legislation’. Missen remained consistent in that course throughout his time in the Senate.

Missen believed that the Senate should refuse supply bills only in ‘extraordinary circumstances’, and he had no doubt that the Opposition’s blocking of supply in 1974 was ‘disastrous’. He took the same view during the crisis of 1975 and expressed that opinion ‘very strongly’ to his party leader, Malcolm Fraser, and in the party room in October 1975. Missen considered that such drastic action undermined political stability, and reduced respect for a government which came to power in this way; he also believed that in both cases denial of supply was premature because the Opposition would have won an election held at the normal time. Although Missen’s views on the subject were no secret, as no other members of the parliamentary party were prepared to make a stand with him, he concluded that it would be futile to vote against his party in the Senate on the issue of the deferral of supply. When the Whitlam Labor Government was dismissed by the Governor-General in November 1975, Missen was ‘shaken’ by the event itself, and ‘disgusted’ by the triumphalism of his colleagues.

In September 1975 Missen had written to shadow Attorney-General Greenwood suggesting a constitutional amendment to ensure that any casual Senate vacancy was filled by a member of the same party as the former incumbent. Missen believed that the Senate had ‘lost credibility’ in the wake of the controversial appointments of senators Bunton and Field to replace Labor senators during 1975, and argued that it was ‘essential that representation should not be distorted by the use of the replacement of vacancies to thwart the will of the people’. A proposal embodying Missen’s suggestion was one of three constitutional amendments carried at a referendum in May 1977.[2]

In 1974 Missen joined the Senate Standing Committee on Constitutional and Legal Affairs. Later that year, the committee considered the Whitlam Government’s Family Law Bill. Most of the committee’s recommendations were unanimous and supported the principal provisions of the bill, including the introduction of no-fault divorce following a period of separation (though there was disagreement about the length of separation), the establishment of a family court, and provisions for the joint custody of children. The committee’s report was tabled in the Senate in mid-October 1974; two weeks later, when the second reading debate on the bill resumed, Missen was the first speaker. He strongly supported the bill in principle, while foreshadowing amendments in accordance with the recommendations of the committee. As a lawyer, he had personal knowledge of the shortcomings of the existing legislation: ‘the keeping of two people together, bickering and fighting, has led to many unfortunate effects upon the children’. He characterised any attempt to apportion blame in a divorce as ‘an exercise in futility and an exercise in creating animosities’, and concluded by emphasising that he believed ‘strongly in the institution of marriage, in seeing it preserved and in making it workable’. Missen would later nominate this speech as the most significant of his Senate career.

Missen was a frequent contributor to debate at the committee stage of the bill, and carried a number of amendments, including a provision for the establishment of state family courts funded by the federal government. The principal recommendations of the Constitutional and Legal Affairs Committee were accepted by the Senate in November 1974, the bill passed through the House of Representatives without major amendment in May 1975, and the Family Law Act came into effect in January 1976.[3]

Missen chaired the Constitutional and Legal Affairs Committee for seven years (1976–83). During that time the committee investigated a variety of questions, including the preservation of the right of the Senate to amend appropriation measures other than those defined as the ‘ordinary annual services of government’ (1976); whether the High Court should offer advisory opinions (1977); the processing of law reform proposals in Australia (1979); and the feasibility of a compact between the Commonwealth and Aboriginal people (1983).

Another reference to the Constitutional and Legal Affairs Committee resulted in the creation of a vital new committee, with Missen as its guiding spirit. In November 1978 a report of the Constitutional and Legal Affairs Committee recommended the establishment of a joint parliamentary committee to scrutinise proposed legislation for any provisions which might adversely affect the rights of individuals. It took a year for the Fraser Government to respond, and when it did, the government dismissed the proposal as ‘unacceptable’, citing the possibility of delays to legislation and suggesting that Parliament already possessed ‘ample opportunities for the examination of legislation’. The Opposition—with the notable exceptions of senators Michael Tate and Gareth Evans—was also initially unsupportive. Missen expressed amazement at the government’s response, describing it as ‘insulting’, but he persevered. In November 1981 his motion for the establishment of the Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills, incorporating an amendment moved by Senator David Hamer that proposed that the work of the new committee be done on an experimental basis by the Constitutional and Legal Affairs Committee for six months, was passed in the Senate, despite ‘desperate government resistance’, six government senators joining Missen in crossing the floor. In the following year, also on Missen’s motion, the committee was set up as a separate Scrutiny of Bills Committee. Hamer found that the committee ‘was greatly envied in other Westminster-style Parliaments which knew about it’. Missen was the chairman from the committee’s inception until 1983.

Missen was also a prominent member of another Senate scrutiny committee, the Standing Committee of Regulations and Ordinances, which he chaired from 1978 until 1980. He described the committee as ‘one of the least publicised but vital and continuous activities of Parliament’, and said that it was intended to be ‘a watchdog over the possible misuse of executive power’. Missen organised and chaired the ‘brilliantly conceived and managed’ inaugural Commonwealth Conference of Delegated Legislation Committees, held in Canberra in 1980. Missen’s role at the conference won him international standing for his work on parliamentary scrutiny. [4]

In the Senate, on 30 July 1974 Missen sought an explanation from Attorney-General Lionel Murphy for the Whitlam Government’s ‘prolonged delay’ in introducing freedom of information legislation, first promised in January 1973, and he pursued the issue over the next four years. In March 1977 he welcomed the Fraser Government’s announcement of a freedom of information bill. Missen noted that: ‘This is a matter for which many of us in the Senate and in the other House have worked for many years because we believe it is essential that there be legislation which makes available, as of right, a mass of material which the Government has but which … does not become available to the public so that there can be full and rational discussion of issues’.

By early 1978 Missen had begun to doubt the commitment of the Fraser Government to comprehensive freedom of information legislation. In April 1978 he put on notice thirty-five questions to various ministers seeking reasons for denial of public access to departmental documents. He was unimpressed by the mostly negative responses, and later pointed out that the reasons offered for not producing documents were likely to be the same excuses for refusal of documents to be provided in the impending Freedom of Information Bill; his fears were justified when the bill was introduced into Parliament in June 1978. The government responded to criticisms of the bill by referring it to the Constitutional and Legal Affairs Committee. Missen, as chair of the committee, expected ‘to conduct the most thorough and extensive inquiry that has ever been carried out by a Senate committee’. The committee’s unanimous report of more than 400 pages contained ninety-three recommendations and took more than a year to complete.

In 1980 the government rejected or deferred two-thirds of the committee’s recommendations and the bill lapsed. When the Fraser Government introduced a new Freedom of Information Bill in April 1981, Missen published a scathing critique: he detailed the bill’s ‘seven deadly sins of omission’, arguing that these shortcomings made ‘nonsense of public expectations that government documents will be opened up to the public, and will give senior bureaucrats ready weapons for denying access to inconvenient facts’. Missen had already warned that he and other Liberal senators were prepared to cross the floor in support of amendments for a ‘stronger bill’, and they did so on 7 May 1981, when the defection of five Liberal senators, including Missen, resulted in the government being twice defeated. The government, knowing it would lose control of the Senate after 30 June, entered into negotiations with Missen and his supporters. Missen agreed to a compromise solution in which the government accepted a little less than half of the amendments moved in the Senate. Missen later explained that this ‘was a deliberate choice to take a Bill that was not strong enough but finally to get something into operation and hope that in the new parliament, we could improve it. This did, in fact occur’. Missen’s biographer, Anton Hermann, considered the Freedom of Information Act to be Missen’s ‘finest achievement in law reform’.[5]

Missen’s commitment to human rights and civil liberties had an international dimension, and he was a member and later chairman of Amnesty International’s Australian Parliamentary Group. During his first days in the Senate, Missen raised the issue of ‘the persecution of the Jewish community in Syria’. He was a long-standing opponent of apartheid in South Africa. While Missen spoke out, forcefully and often, against human rights violations, he was also, in the words of his colleague, Senator Hill, ‘an activist, not just a talker’. On a visit to the USSR in 1976, Missen smuggled out a copy of a report by Russian dissidents on human rights abuses in the Soviet Union, and had it released. In the Senate, in 1977, he supported an unsuccessful Labor Party motion for the establishment of a select committee to examine allegations of Indonesian atrocities in East Timor. In 1984 Missen said that refugees from West Papua (then called Irian Jaya) should not be returned from Papua New Guinea against their wishes, and he was incensed by the Australian government’s apparent reluctance to protest to Indonesia over the treatment of the indigenous population in West Papua. He was shocked by violence meted out to Tamils in Sri Lanka, and suggested that consideration be given to the imposition of sanctions against the Sri Lankan government. Missen’s last speech in the Senate was concerned with the problems of Afghan refugees displaced after the Russian invasion of 1979. Missen believed that the Australian government was doing too little to resettle Afghan refugees in Australia.[6]

During December 1982 Missen voted against the Fraser Government on a number of occasions in support of the Australian Democrats’ World Heritage Properties Protection Bill, which sought to give effect to the World Heritage Convention, ratified by Australia in 1974. By protecting Australian cultural and natural heritage sites, the bill was intended to prevent the damming of Tasmania’s Gordon River and the construction of the Gordon-below-Franklin Dam. Five months later, Missen again crossed the floor to vote for the Hawke Labor Government’s World Heritage Properties Conservation Bill 1983, which had the same aim as the Democrats’ 1982 bill. He described the High Court decision of July 1983, which upheld the legislation, as ‘one of the great reaffirmations of Australian nationhood’.[7]

In September 1981 Missen spoke strongly in support of the aims of a private senator’s bill, the Queensland Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders (Self-Management and Land Rights) Bill, put forward by Labor’s Susan Ryan at a time when the Bjelke-Petersen state government had abolished some Aboriginal reserves in Queensland and was threatening to abolish others. During his speech, Missen noted that in 1975 the Senate had adopted a resolution urging the Australian government to ‘admit prior ownership’ of the land by its indigenous people:

One of the things we ought to do in acknowledging land rights in Queensland surely is to accept this principle as the first essential, thus showing that we are prepared to take some action, to take some stand, to incur some wrath in certain parts of Australia and to fight to ensure that their rights in those areas are protected.[8]

The bill passed the Senate, but did not proceed through the House of Representatives.

Late in his Senate career, Missen declared himself to be an ‘unreserved supporter’ of the work of five royal commissions into organised crime, conducted between 1973 and 1984, and of the permanent body established to continue their work, the National Crime Authority. He declared that ‘many people’ did not ‘really understand the extent of organised crime in this country. I don’t think they appreciate that basic civil liberties are about having a country free of corrupt officials’. In 1984 Missen wrote a minority report to the Constitutional and Legal Affairs Committee’s report on the National Crime Authority Bill 1983, in which he advocated greater powers for the NCA, and suggested that its activities be monitored by a permanent parliamentary committee. Missen became deputy chair of the newly-established Joint Committee on the National Crime Authority in 1984. Missen’s crusading stance in support of the NCA dismayed some who could not reconcile his views with his long record as an outspoken supporter of civil liberties and human rights. However, to his friend Senator Chaney, Missen’s opinions on how to deal with organised crime were proof of his ‘ability to look at the facts and to analyse them, and not to be locked into a position’.[9]

Despite multiple floor-crossings and other dissents from the party line, Missen was sensitive to portrayals of himself as a ‘rebel’ or ‘maverick’, and vehemently repudiated such descriptions, even to the point of taking legal action. As far as he was concerned, his approach to government legislation was ‘vigorous and constructive’. Neither was Missen devoid of ambition. He would have liked to have been Attorney-General, but he accepted that under Malcolm Fraser’s leadership he was not going to be offered a ministerial post. Missen was crushed when an anticipated appointment as shadow Attorney-General under Andrew Peacock did not eventuate after the 1984 election.

During his last few years in the Senate, Missen’s health was failing. He suffered from diabetes and heart problems, but kept on working until he died in his sleep at his home in Balwyn, Melbourne, on 30 March 1986, survived by his wife. Eight days later, twenty-nine senators and eighteen members of the House of Representatives from all parties paid tribute in the Parliament to Missen. Some of them admitted that he could be a ‘difficult’ colleague, and an ‘irritant’. Liberal Senator Chris Puplick recalled that it was not easy to make a speech ‘and have Alan Missen sitting beside me muttering under his breath: “You have sold out again, haven’t you?” ‘ Senator Peter Baume said of Missen: ‘As a person he was singular because of his uncompromising and quite predictable adherence to his principles as he saw them. No one else in this place in my time has approached his determination to act in this way’.

There were different views of his effectiveness: Liberal MHR Ian Macphee suggested that Missen might be judged ‘to have been a fine parliamentarian but a poor politician’. Senator David Hamer, writing some years later, believed that Missen’s ‘method of presentation lost him much support. He carried on as if he were the only saintly figure, which antagonised many people’. Yet Missen’s capacity to irritate, his tenacity, and commitment to principle gained remarkable results from the backbench. There was also his personal example. Australian Democrats senator Colin Mason, recalled Missen’s comment to him before crossing the floor to support the World Heritage Properties Protection Bill in 1982: ‘I am going to get into great trouble over this. I don’t care. I have done what I thought was right’. Mason argued that Missen’s abrasive qualities, and his individualism, compelled parliamentary debate to move beyond party politics into considerations of principle and the common good: ‘It caused difficulties. I say great, that that was a good thing to have happened. There should be more of it’.

Central to Missen’s incisive contributions to so many subjects was his prodigious capacity for work, including ‘assiduous attention to the details and to the facts’ of any matter before him. This quality was acknowledged by many of his colleagues. More than 350 boxes of Missen’s papers, held by the National Library of Australia, are a testament to his energy and range of interests. Liberty Victoria (formerly the Victorian Council for Civil Liberties) commemorates his work through the annual Alan Missen Oration.[10]

[1] This entry draws throughout on Anton Hermann, Alan Missen: Liberal Pilgrim, The Poplar Press, Woden, ACT, 1993 [Hermann], and on a transcript of an interview with Alan Joseph Missen by Toby Miller, 4–7 March 1980, NLA TRC 732 [NLA Interview]; ‘Questionnaire’ completed 5 May 1985 for Parliament’s Bicentenary Publications Project, NLA MS 8806; Argus (Melb.), 22 Aug. 1951, p. 2; Age (Melb.), 31 Aug. 1951, p. 8; Patrick O’Brien, The Liberals: Factions, Feuds and Fancies, Viking, Ringwood, Vic., 1985, pp. 52–63.

[2] CPD, 14 Aug.1974, p. 885; A. Missen, ‘The Senate, its future role in Australian politics’, July 1975, Missen Papers, NLA MS 7528, Box 342; Transcript, Radio 2GB ‘Talkback’, 12 Nov. 1985; NLA Interview; Paul Kelly, November 1975, Allen & Unwin, Syd., 1995, pp. 111–15, 236–240; CPD, 25 March 1982, pp. 1239–41; Hermann, pp. 106–10, 118–20; AFR (Syd.), 31 March 1977, p. 3.

[3] Senate Standing Committee on Constitutional and Legal Affairs, Report on the Law and Administration of Divorce and Related Matters and the Clauses of the Family Law Bill 1974, Canberra, Oct. 1974; CPD, 15 Oct. 1974, pp. 1705–9, 29 Oct. 1974, pp. 2031–9, 26 Nov. 1974, pp. 2769–82; Hermann, pp. 94–101; Henry Finlay, To Have But Not To Hold, Federation Press, Sydney, 2005, p. 380.

[4] Senate Standing Committee on Constitutional and Legal Affairs, Report on Scrutiny of Bills, Canberra, Nov. 1978; CPD, 22 Nov. 1979, pp. 2793–8, 17 Nov. 1981, pp. 2243–53, 19 Nov. 1981, pp. 2418–28, 25 May 1982, pp. 2341–2; Denis Pearce, ‘Opening address’ in ‘Ten Years of Scrutiny: a seminar to mark the tenth anniversary of the Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills’, Parliament House, Canberra, 25 Nov. 1991; David Hamer, Memories of My Life, Melb., 2002, pp. 564–5; Hermann, pp. 142–7; CPD, 8 May 1986, pp. 2630–2.

[5] CPD, 30 July 1974, pp. 532–3, 10 March 1977, pp. 83–7, 22 Feb. 1978, pp. 59–60, 28 Sept. 1978, pp. 1109–10; Senate, Notice Paper, 5 April 1978, pp. 266–72; Hermann, pp.123–30; Age (Melb.), 5 July 1978, p. 11; Senate Standing Committee on Constitutional and Legal Affairs, Freedom of Information, Canberra, Nov. 1979; CPD, 6 Nov. 1979, pp. 1880–4, 11 Sept. 1980, pp. 797–815; SMH, 13 Feb. 1981, p. 9; Press Release, Senator Alan Missen, 4 April 1981; CT, 9 April 1981, p. 14.

[6] CPD, 1 Aug. 1974, pp. 692–3, 20 Nov. 1974, pp. 2574–7, 18 Aug. 1976, pp. 150–7, 24 March 1977, pp. 536–40, 27 Aug. 1980, p. 425, 19 May 1982, pp. 2111–3, 18 Nov. 1982, pp. 2471–2, 9 May 1984, pp. 1870–2, 31 May 1984, pp. 2304–7, 9 May 1985, pp. 1708–12, 8 April 1986, p. 1415; CT, 5 June 1984, p. 10; Press Release, Australian Council for Overseas Aid, 29 July 1983; CPD, 12 Oct. 1983, pp. 1515–17, 5 Nov. 1985, p. 1590, 20 March 1986, pp. 1323–7, 8 Nov. 1979, pp. 2099–2111, 19 Nov. 1979, pp. 2503–15.

[7] CPD, 2 Dec. 1982, pp. 3112–15, 17 May 1983, pp. 482–3; Hermann, pp. 157–8; Senate Standing Committee on Constitutional and Legal Affairs, Report on Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders of Queensland Reserves, Canberra, Nov. 1976.

[8] CPD, 24 Sept. 1981, pp. 1047–54.

[9] WA (Perth), 10 Jan. 1985, p. 9; Senator Alan Missen, ‘Minority Report’ in Senate Standing Committee on Constitutional and Legal Affairs, The National Crime Authority Bill 1983, Canberra, May 1984, pp. 109–137; CPD, 6 June 1984, pp. 2677–81, 8 April 1986, p. 1395.

[10] Herald (Melb.), 11 Nov. 1976, p. 3; National Times (Syd.), 3–9 Jan. 1986, p. 8; Hermann, p. 166; ‘Questionnaire’ 5 May 1985; CPD, 8 April 1986, pp. 1393–1415; Hamer, Memories of My Life, p. 608; Weekend Australian (Syd.), 27/8 Jan. 1979, p. 2; Media Release, Senator Alan Missen, 13 Feb. 1986; Missen Papers, NLA MS 7528.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, Vol. 4, 1983-2002, Department of the Senate, Canberra, 2017, pp. 405-410.