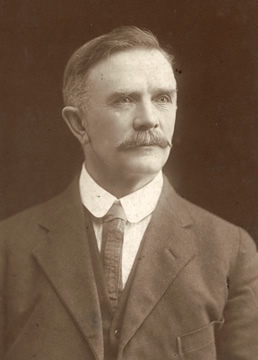

GIBSON, William Gerrand (1869–1955)

Senator for Victoria, 1935-47 (Australian Country Party)

William Gerrand Gibson, farmer and storekeeper, was born at Gisborne, Victoria, on 19 May 1869, the son of Scottish‑born parents, David Gibson, a farmer, and his wife Grace, née Gerrand. Gibson was educated locally, then farmed with his father before setting up on his own as a storekeeper at Romsey and Lancefield. Becoming a successful businessman, Gibson turned his attention to public affairs, serving as president of the local branch of the Australian Natives’ Association and of the Romsey and West Bourke Agricultural Society. In 1910 Gibson, a progressive farmer, purchased land at Lismore, which he developed into a mixed farm and eventually the successful grazing property, ‘Cluan’. Gibson’s growing interest in rural politics was reflected in his involvement with the increasingly powerful Victorian Farmers’ Union (VFU), first established in 1914; at one time he became secretary of its Lismore branch, and was also a member of its central executive.

In December 1918 Gibson stood at the first federal by-election after the introduction of preferential voting for the House of Representatives. The Nationalist Party had pushed the legislation through to ensure preferential voting was in place prior to the by-election, thus advantaging the non-Labor cause. Arguing that for too long primary producers had been subjected to ‘taxation without proportionate representation’, Gibson defeated four other candidates (including the future ALP Prime Minister, J. H. Scullin) to win the seat of Corangamite as an independent, endorsed by the VFU. He thus became the VFU’s first representative in the Commonwealth Parliament. The Lismore Advertiser was delighted, observing that Gibson’s victory meant that the Government, allegedly awash with city lawyers, would at last be exposed to forthright criticism concerning ‘the plague of billet hunters, political adventurers and profiteers who have been fleecing the primary producers’. Gibson held Corangamite for the VFU at the 1919 general election, and for the Country Party at the elections of 1922, 1925 and 1928. He was defeated in 1929, but regained the seat in 1931, holding it until 1934.[1]

During World War I, small farmers became increasingly dissatisfied with Nationalist Government policies on the marketing of primary products, especially wheat. Agitation for a separate rural voice in Parliament increased and, on 22 January 1920, at a meeting in Melbourne chaired by Gibson, the Australian Country Party was formed. The December 1922 federal election delivered the balance of power to the Country Party in the House of Representatives. With ‘the flag of revolt’ flying, the Country Party leadership rejected Prime Minister W. M. Hughes’ offer of portfolios in what would have been his fifth administration. A Nationalist–Country Party Government was then formed, the Country Party leaders having successfully vetoed Hughes’ inclusion in the coalition ministry that took office in February 1923.

Closely involved in forging the coalition between the Nationalists and the Country Party, in January 1923 Gibson had become the unanimous choice of his parliamentary colleagues for the post of deputy leader of the Country Party, and immediately joined the ministry. As Postmaster-General (February 1923 to October 1929) and Minister for Works and Railways (December 1928 to October 1929), he made a significant contribution to the Bruce–Page Government.[2]

From 1921 to 1922 Gibson had served on a joint select committee appointed to investigate Australia’s wireless communications. As Postmaster-General he now introduced several important reforms that did much to lessen the isolation of rural dwellers. These initiatives included the expansion of country postal and wireless communication services, the construction of new post offices, and the establishment of a rural automatic telephone exchange system, a reform Gibson came to regard as ‘my baby’. Gibson believed that the Postmaster-General’s Department should concentrate on providing a high standard of service to the public rather than on amassing large profits. He felt that greater savings and improved service provision could best be achieved, not by constructing numerous new post office buildings or increasing postal officers’ salaries, but by creating an extensive night-and-day automatic telephone network. Gibson’s ambitious vision of the future for communications encompassed telephone trunk services across the Australian continent and beam wireless links with several nations of the northern and southern hemispheres. On becoming Postmaster-General, he declared that he was not a ‘revolutionary’ with plans to turn his department upside down. Nevertheless, when he left office Gibson (along with his appointee as head of the Postmaster-General’s Department, H. P. Brown) had transformed the Australian postal and telecommunications system.

In his first speech as an MHR, Gibson had criticised unnecessary duplication between Commonwealth and state taxation departments. He believed that increased immigration was essential to Australia’s development, and called for Commonwealth government assistance to rural industries on the grounds that their demise would spell doom for Australian manufacturing. He was convinced that Australia must widen its trading links. Gibson also favoured the establishment of an Australian broadcasting commission, over which the federal Government would have ‘negligible’ oversight.[3]

In 1934 the Victorian Country Party attempted to force its federal parliamentarians to sign a pledge that would have imposed far-reaching organisational control over members and senators. All Victorian Country Party representatives, including Gibson and Senator R. C. D. Elliott, refused to sign, and announced that they would stand as endorsed, but unpledged, Country Party candidates. Late in the campaign, Gibson decided not to re-contest Corangamite and accepted instead an offer from the United Australia Party to join a UAP–CP Senate ticket, an invitation not extended to Elliott owing to his criticism of the tariff policies of the Lyons Government. Gibson secured a Senate seat and the UAP wrested Corangamite from the Country Party. The Country Party leader, Earle Page, believed that Gibson’s Senate place should have gone to Elliott, who had run as an unendorsed Country Party candidate, and lost. Gibson was temporarily excluded from the Country Party, but he was unrepentant. He declared that ‘four hundred thousand people put me into the Senate, and a dozen people exclude me from the Party’, adding that he could represent the interests of those who elected him even if he did not attend party meetings.[4]

In the Senate Gibson served on several committees’ the most important being the Joint Committee on Wireless Broadcasting (1941–42), dubbed the ‘Gibson Committee’ because of his vigorous leadership as chairman. The committee, which received a wide-ranging brief, was empowered to consider changes in the laws and practices relating to the control of broadcasting. After ‘nine months of hard and amicable work’, it produced a report containing seventy-one recommendations. Most pertained to the ABC, the main point of division among members deriving from the expressed intention of the three ALP members that Australia’s commercial broadcasting should be nationalised. The report’s principal recommendations, which left the ABC intact, were embodied in the Australian Broadcasting Act 1942, and included the appointment of a parliamentary committee to oversee the operations of the ABC. On 3 September 1942, the Joint Standing Committee on Broadcasting was appointed.

Gibson favoured the broadcasting of parliamentary proceedings, providing the process was monitored by a joint committee of the Parliament, and in 1946 became a member of the new Joint Committee on the Broadcasting of Parliamentary Proceedings. The principles governing parliamentary broadcasting were established at the committee’s first meeting on 5 July 1946. On 10 July the House of Representatives was ‘on the air’ for the first time, the Senate following on 17 July.[5]

Gibson possessed a particular knowledge of Australia’s primary industries, especially wheat, flax, mutton and lamb, dairying and wool. He regarded the ALP Government’s proposed Wheat Industry Stabilization Bill 1946 as ‘the first step towards the nationalization of primary production’. He claimed the bill provided ‘not for stabilization but for sheer confiscation’ and put the wheat farmer in the position of having ‘a dog-collar round his neck with a chain attached to it’. He questioned ‘the ideal of the home market’ on the grounds that ‘the world’s market is the only market available to Australia’. Nevertheless, he deplored the ‘economic nationalism’ of the 1930s that had resulted in overproduction and a world glut of primary products such as wheat. Speaking on the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization Bill 1944, he emphasised the necessity of placing primary industry on a sound basis, and of securing global markets for Australian primary products. He also warned of the possible dangers if international agencies placed worldwide limits on Australian primary production and exports. With the directness of the practical farmer, Gibson made clear his objection to large-scale economic planning by experts (government by economists) and stressed the need for greater involvement by primary producers in decisions governing the production and marketing of their produce. Gibson described the Commonwealth Bank Bill 1945 as an attempt to eliminate the private trading banks by ‘a process of strangulation’.

In mid-1946, at the age of seventy-seven, he indicated that he would not seek re-election for a third term.[6] Gibson, whose recreations included shooting, fishing and golf, lived out his remaining years at Cluan. On 4 November 1896, at Riddells Creek near Macedon, he had married, in a Presbyterian ceremony, Mary Helen Young Paterson, daughter of John Paterson, a farmer. Survived by the only son of the marriage, David Ian, and a daughter, Margaret Lyle, Gibson died in the Lismore Bush Nursing Hospital on 22 May 1955 and was buried in the Lismore Cemetery. Gibson’s wife and his daughter Grizelda Watson (Grace) predeceased him.

Soft-spoken and taciturn in manner, Gibson was remembered for his ‘keen sense of justice and fair play’, and ‘his good humour, his tolerance, and his objectivity in debate’. While he had once observed that ‘there is more than one side to every question of politics’, throughout his life he had remained totally committed to the causes he espoused.[7]

[1] L. Lomas, ‘Gibson, William Gerrand’, ADB, vol. 8; Romsey Examiner, 11 Feb. 1910, p. [2]; Farmers’ Advocate (Melb.), 20 Nov. 1919, p. 5; G. S. Reid and Martyn Forrest, Australia’s Commonwealth Parliament 1901–1988, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1989, pp. 116-18; Geoffrey Sawer, Australian Federal Politics and Law 1901–1929, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1956, pp. 158-9; Ulrich Ellis, A History of the Australian Country Party, MUP, Parkville, Vic., 1963, pp. 43-4; B. D. Graham, The Formation of the Australian Country Parties, ANU Press, Canberra, 1966, pp. 128–9; L. Lomas, ‘Graziers and Farmers in the Western District, 1890–1914’, Victorian Historical Journal, Feb. 1975, pp. 250–82; Lismore Advertiser, 20 Nov. 1918, p. [7], 23 Dec. 1918, p. [6].

[2] Ellis Papers, MS 1006/6-2, NLA; Lomas, ‘Graziers and Farmers in the Western District, 1890-1914’, pp. 281-2; Land (Syd.), 30 Jan. 1920, p. 9; Ellis, A History of the Australian Country Party, pp. 50–4; Earle Page, Truant Surgeon, ed. Ann Mozley, A & R, Sydney, 1963, pp. 90–9; Argus (Melb.), 2 Feb. 1923, p. 9; SMH, 17 Jan. 1923, p. 13.

[3] CPP, Joint Select Committee into the Proposed Agreement with Amalgamated Wireless (Australasia) Limited, report, 1922; CPD, 15 Aug. 1923, pp. 2808-10, 21 July 1926, pp. 4441-3, 6 Oct. 1927, pp. 340-1, 8 Dec. 1927, pp. 2903-8, 28 Sept. 1944, p. 1650, 6 Sept. 1928, pp. 6497–503, 30 Apr. 1942, p. 646, 30 June 1938, p. 2912, 30 May 1947, p. 3195; Ann Moyal, Clear Across Australia: A History of Telecommunications, Thomas Nelson, Melbourne, 1984, pp. 117-21, 126, 139; Lismore Advertiser, 21 Feb. 1923, p. [5]; CPD, 10 July 1919, pp. 10619-20, 1 July 1925, pp. 572-3, 15 Nov. 1932, p. 2342, 10 Mar. 1932, p. 967.

[4] Australian Country Party Monthly Journal (Syd.), 1 Aug. 1934, p. 6, 1 Oct. 1934, pp. 3, 5, 11, 15; Geoffrey Sawer, Australian Federal Politics and Law 1929–1949, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1963, pp. 71-2; Ellis, A History of the Australian Country Party, pp. 4, 206-7, 226, 335; Argus (Melb.), 24 Sept. 1935, p. 3.

[5] CPP, Joint Committee on Wireless Broadcasting, report, 1942; Alan Thomas, Broadcast and Be Damned: The ABC’s First Two Decades, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1980, pp. 123-5; Sawer, Australian Federal Politics and Law 1929–1949, p. 136; K. S. Inglis, This is the ABC: The Australian Broadcasting Commission 1932–1983, MUP, Carlton, Vic., 1983, pp. 105-6; CPD, 30 Apr. 1942, pp. 645-57, 20 June 1946, p. 1622; Senate, Journals, 5 & 17 July 1946; J. R. Odgers, Australian Senate Practice, 3rd edn, Commonwealth Government Printer, Canberra, 1967, pp. 382-3.

[6] CPD, 15 Oct. 1943, p. 646, 1 July 1941, pp. 571-4, 1 Aug. 1946, p. 3456, 3 Dec. 1935, p. 2332, 21 Nov. 1939, p. 1300, 24 Nov. 1944, pp. 2105-6, 29 June 1945, pp. 3859-65, 24 July 1945, pp. 4392-5; Herald (Melb.), 5 June 1946, p. 3.

[7] Age (Melb.), 23 May 1955, p. 3; Romsey Examiner, 4 Aug. 1944, p. [3]; CPD, 30 Aug. 1944, pp. 389-90, 24 May 1955, p. 375, 30 May 1947, p. 3195.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 2, 1929-1962, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Vic., 2004, pp. 126-129.