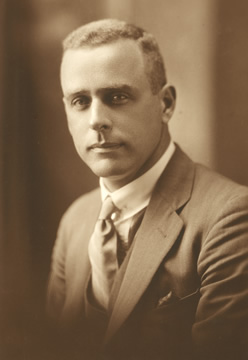

HARDY, Charles (1898–1941)

Senator for New South Wales, 1932–38 (Australian Country Party)

Charles Hardy, was born at Wagga Wagga, New South Wales, on 12 December 1898, the first son of Charles Hardy, a contractor, and Mary Alice, née Pownall, of Young. He was the third successive son of his family to bear, or at least use, the name, Charles Hardy. His father and grandfather were successful businessmen and pioneers of the district, and the son, throughout his life, continued to develop the family enterprises, especially in the timber industry. Hardy was educated at Wagga Wagga High School and went on to Geelong Grammar, which he left in 1915 to be apprenticed as a carpenter. He enlisted in the AIF in January 1917, embarking with the 1st Field Company Engineers in June. He was gassed in France and returned in 1919 to Australia and the family business, Charles Hardy and Company, in Wagga. According to Table Talk, in 1924 he went to the United States of America, returning some time later with £35 000 worth of machinery for dressing timber from the forests around Tumbarumba in New South Wales. It seems he also acquired contracts for building the new city of Canberra. A man of considerable energy, he established the Wagga Country Golf Club and was a leading light in the local Returned Sailors’ and Soldiers’ Imperial League of Australia.[1]

In the secessionist and small state movements that emerged across Australia from the late 1920s—in response to the perceived threats not just of J. T. Lang and communism but equally of an incompetent, city-based conservatism that supported manufacturers with high tariff walls—the Riverina Movement was the most radical. It was avowedly separatist at its height, and its most extreme and articulate exponent was Hardy, thirty-two years old when he met Prime Minister Scullin in 1931 to press his movement’s demands. ‘We were told’, a later critic said, ‘that he was destined to lead the people of New South Wales, and of Australia generally, out of the depression’. To his followers he was indeed the leader of the Riverina Movement (though described as ‘chairman’); to others he was a Cromwell or Mussolini in the making.

Hardy’s leadership of the diverse groups who flirted with the All for Australia League and then coalesced to form the United Country Movement during 1931 presented the leaders of the existing parties with a considerable challenge in the turbulent period from 1929 to 1931 when the Labor Party broke and fell and the United Australia Party took shape under Joseph Lyons. In April 1931 Lyons, promising a constitutional convention to appease groups such as the Riverina Movement, commended Hardy as an ‘Australian patriot’ who, with his followers, should be helped ‘to a position where they will have something more to say in government than they do today’. Earle Page referred to Hardy’s ‘great driving force and organizational ability’. This led by August to the merger of the conflicting rural parties. It also led to Hardy’s selection as a Senate candidate on a combined UAP–Country Party ticket in November 1931, at the cost of displacing the sitting Nationalist senator, W. L. Duncan. But as Page noted, ‘the United Country Movement had thus, in effect, been absorbed by the Australian Country party’.[2]

That was true, though Hardy’s campaigning in the election of 1931 retained the fervour of his earlier regional meetings. ‘As every one knows’, he later recalled in the Senate: ‘I played a vital part in that election. I threw myself into the contest with all the energy at my command, in nineteen days addressing 51 meetings and travelling between 8000 and 10,000 miles, by air, to keep my engagements’. His advertised appearances on successive days included some tight schedules. For instance on Wednesday, 2 December, he was at ‘Narrabri at 11 a.m., Walgett at 3 p.m., and Moree at 8 p.m.’. Thursday saw him at ‘Inverell at 11 a.m., Tenterfield at 3 p.m., and Armidale at 8 p.m.’. As the third candidate on the combined ticket he was easily elected, despite, on his own account, advising electors to vote against the Senate ticket.

Before taking his seat in the Senate, Hardy attracted criticism within it. His remarks to the press that there was a ‘great gulf’ between the United Country Party and the Nationalists were immediately aired by Labor’s Arthur Rae and firmly rebutted by George Pearce. Hardy also continued his colourful attacks on the New South Wales Lang Government, declaring it to be ‘plumbing further depths of infamy’. By the time Hardy took his seat, however, Lang had been dismissed. As Pearce later said, the federal Government had ‘done its job too well for the honourable senator; it has removed from office the Lang Government which was the beginning and end of the honourable senator’s policy’. By the end of 1932 a conference between members of the United Country Movement and Riverina members of Parliament decided that the Riverina Movement to which Hardy had given so much passionate fervour was to be absorbed into the Country Party.[3]

Certainly Hardy’s early period as a senator was more tentative than his followers might have expected. He spoke only briefly in his first session, reserving his fire for debates in mid-1933 over the tariff policies of the Lyons Government, which, he argued, betrayed the Country Party and the agreements it had reached with the UAP in the campaign of 1931. (By mid-1933 he had also tendered his resignation as chairman of the central executive of the Riverina Movement.) In the approach to the election of 1934 he maintained his attacks on Lyons, asserting that the early election was unjustified and that the ‘Lyons Government would go out with a bump’. At a heated meeting of the Wagga branch of the UAP in October 1933 it was suggested that Hardy might resign his Senate seat. By then he had revealed some pessimism about the nature of the Senate and, perhaps, his place in it. So far ‘from the Senate being representative of the States or the rural interests’, he said after a year as a senator, ‘it is simply an echo of city interests that have more than their fair share of representation in another place’. His attendance in the chamber, especially in his early years, and in divisions was below the average for the Senate as a whole, or for his cohort, and his business concerns must partly explain that. In 1933 Hardy Ltd (as his firm had become) had faced liquidation and during 1934 his father died, as did an uncle who was a partner in the firm. But the interests of the Riverina remained paramount at all times. He was a vigorous campaigner for the 1934 federal election, as well as raising funds to present the Riverina’s case for the Royal Commission on New States.[4]

The negotiation of the Lyons–Page coalition in November 1934, and subsequently the adoption of some country-oriented policies, especially the development of primary industry marketing schemes, seems to have warmed Hardy anew to his mission. He became Leader of the United Parliamentary Country Party in the Senate in October 1935, though not without causing something of a fracas within Western Australian Country Party ranks. An absent colleague who had in effect also served as a leader, W. Carroll, opposed Hardy’s appointment. Another, E. B. Johnston, accusing Hardy of falsely claiming the title of leader, withdrew from the party to call himself a ‘Western Australian Country Party senator’, though the designation does not appear to have stuck. Johnston, conscious of the Western Australian secession issue, complained that local party rules ‘preclude[d] Western Australian Country party senators from following any party leader in a senate established for the protection of the rights of the people of the weaker States’. There was, he said, ‘no Leader of the Country party in the Senate’, and claimed Western Australians looked on the Senate as ‘our one stronghold’. For his part, Hardy explained that two nominations had been received for the position—his, and Senator Johnston’s—and they had ‘decided to pair in the voting, thus allowing the other three honourable senators present—Senators Cooper, Badman and Abbott—to make the decision’.

Hardy remained leader until the expiry of his Senate term; for a time his interventions increased markedly in range and frequency. Between his defeat in the election of October 1937 and his departure in mid-1938, Hardy spoke only once and took no part in divisions. He was probably preoccupied with Riverina affairs. In March 1937 he had been appointed leader of the Riverina division of the United Country Party, a position he had held previously, though he had resigned in November 1935, reputedly because of ill health.[5]

After leaving the Senate Hardy worked with the RAAF as an honorary coordinator of works, and then with the Department of Defence Coordination in the early years of World War II. That he did not contest election to the Senate in 1940 was not surprising: in the normal cycle of Senate contests he might have been expected to wait until the following election to reveal any further political ambitions. It seems unlikely that he intended an attempt at re-election, however, though he was certainly young enough. His life ended suddenly in an air crash at Coen, Queensland, on 27 August 1941.

A close personal friend of the Leader of the Country Party, Arthur Fadden, MHR, Hardy was survived by his wife, Alice Margaret Ann, née Trim, whom he had married at St Hilary’s Anglican Church, Kew, a suburb of Melbourne, on 11 July 1922, and two sons, John Charles and Peter Swayne. He was cremated at the Northern Suburbs Crematorium, Sydney.[6]

[1]Andrew Moore, ‘Hardy, Charles Downey’, ADB, vol. 9; W. A. Beveridge, The Riverina Movement and Charles Hardy, BA Hons thesis, University of Sydney, 1954, p. 49; Hardy, C. D.—War Service Record, B2455, NAA; Table Talk (Melb.), 2 Apr. 1931, p. 11; Ulrich Ellis, A History of the Australian Country Party, MUP, Parkville, Vic., 1963, p. 180.

[2] SMH, 2 Mar. 1931, p. 9, 11 Mar. 1931, p. 14, 9 Apr. 1931, p. 11, 13 Apr. 1931, p. 10, 12 Oct. 1931, p. 10, 1 Oct. 1931, p. 9; Ellis, A History of the Australian Country Party, pp. 168–79; SMH, 15 Aug. 1931, p. 13; Earle Page, Truant Surgeon, ed. Ann Mozley, A & R, Sydney, 1963, p. 208.

[3] CPD, 1 June 1933, p. 2029; SMH, 2 Dec. 1931, p. 12; CPD, 9 Mar. 1932, p. 788; SMH, 9 Mar. 1932, p. 14, 10 Mar. 1932, p. 10; CPD, 11 July 1934, pp. 351–2; SMH, 21 Dec. 1932, p. 10.

[4] CPD, 1 June 1933, pp. 2024–37; SMH, 29 June 1933, p. 8, 9 Oct. 1933, p. 11; CPD, 26 May 1933, p. 1888; Australian Country Party Monthly Journal (Syd.), 1 May 1934, p. 5; Beveridge, The Riverina Movement and Charles Hardy, p. 23.

[5] CPD, 3 Oct. 1935, p. 462, 9 Oct. 1935, pp. 522–3; Narrogin Observer, 19 Oct. 1935, p. 7; CPD, 10 Oct. 1935, pp. 598–601, 22 Oct. 1935, pp. 867–9; SMH, 20 Mar. 1937, p. 16, 9 Nov. 1935, p. 22.

[6] SMH, 28 Aug. 1941, pp. 9, 11; CPD, 28 Aug. 1941, pp. 244–5, 27 Aug. 1941, pp. 223–4; Daily Advertiser (Wagga), 28 Aug. 1941, p. 4.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 2, 1929-1962, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Vic., 2004, pp. 410-413.