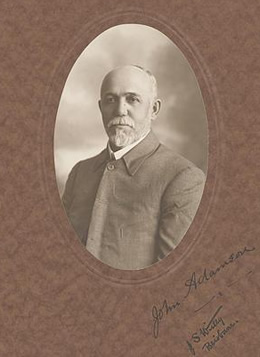

ADAMSON, John (1857–1922)

Senator for Queensland, 1920–22 (Nationalist Party)

John Adamson, Methodist minister, was born on 18 February 1857 at Tudhoe, County Durham, England, the son of Robert Adamson, shoemaker, and his wife, Dorothy, née English. After leaving Tudhoe Public School at the age of ten, he was apprenticed first to his alcoholic father as a shoemaker; then worked as a blacksmith. He became a railway tradesman on the North Eastern Railways, and an active member of the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants. Adamson was a devout adherent of a Christian social gospel with fervent non‑conformist cooperative convictions. Promoting temperance and suspicious of Roman Catholicism, he represented a strand of radical thought and action stronger in England than in the Antipodes. ‘I believe’, he said, ‘in the matter of equality of opportunity and the equitable distribution of wealth’. He declared that there was ‘no man in this world who has got rich on his own exertions’, and that riches were gained only through the exploitation of others.[1]

Familiar with the writings of the Fabian socialists, especially the Webbs and Philip Snowden, Adamson frequently quoted the writings and speeches of neo-Kantian Professor Henry Jones of Glasgow University. Jones’ book, Idealism as a Practical Creed, combined with the commentaries of the American writer, James Russell Lowell, were Adamson’s secular bibles.

Although accepting the discipline imposed on parliamentary representatives of the Labor Party, Adamson was that rara avis in Australian politics, a self-educated intellectual consumed by the fire of the 1914–18 furnace. He would soon declare: ‘I am a free servant of the Labour Party, and some day we will know what a free servant means a great deal better than we do to-day.’

On 4 April 1883, at Bishop Auckland, County Durham, Adamson married Caroline Jones and in January 1884 the couple arrived in Brisbane as bounty migrants on the Duke of Buckingham. For fourteen years, Adamson, who had been converted to Christianity in 1876, was a forthright and caring Primitive Methodist minister at Toowoomba, Mount Morgan, Georgetown, Maryborough, Stanwell, Cooktown, Barcaldine, Ipswich and Boonah. Between 1898 and 1904, he was a minister of the Methodist Church of Australia, and after 1908, a supply minister for the Presbyterian Church at Gladstone, Mackay and Charters Towers.[2]

Adamson was elected Labor MLA for Maryborough in 1907 but, disgusted with Queensland factional politics did not stand in October 1909. Persuaded to stand again by his firm friend, the future premier, T. J. Ryan—‘a man who instinctively gets at your heart’—he narrowly won Rockhampton for Labor at a by-election in February 1911. Following Queensland Labor’s victory in May 1915, Adamson became Secretary for Railways in the Ryan Government. Although a competent minister, Adamson was frustrated that the exigencies of war and office inhibited his ardent desire to improve the lot of the railway workers and, with E. G. Theodore, to expand the state’s railways.[3]

Adamson promoted closer settlement on leased family farms for social and economic reasons, so that ‘men would not lead a nomadic life, moving about without a home, without a wife, without children’. He fought for a more enlightened approach to prisons, mental health, children’s rights and hospital management; also for broader access to education, including the extension of the school-leaving age to sixteen years. On the ‘position of woman’, Adamson advocated equal pay for equal work, economic freedom, equitable terms of divorce, and equal ‘sexual purity’ and social recognition.

He bitterly opposed the introduction of Bible teaching in state schools as divisive and an affront to individual conscience, and, after 1914, became increasingly alarmed at what he perceived to be the growing and ‘undue influence of the Roman Catholics in Parliament [and] in the Public Service of the State’. He pronounced this ‘a real menace to the common weal’. Associating Catholics with the liquor trade and a more relaxed attitude to alcohol, Adamson, a temperance advocate, gave public expression to these misgivings when he launched the Protestant League for the Maintenance of Civil and Religious Rights.[4]

Yet, Adamson may well have survived as a minister and retained his membership of the central political executive of the Queensland Labor Party (1913–16) had it not been for the national crisis over conscription for overseas service during 1916–17. His intense loyalty to ‘King and Country’, and his notion of the war as a cleansing fire that would redeem society conflicted with Queensland Labor’s adamant opposition to Hughes’ referendums. Despite Ryan’s attempts at compromise, Adamson, although vice-president of the Universal Service League, was forced to resign from the ministry and the Labor Party on 2 October 1916, after an impassioned, tearful defence of his own imperial philosophy. He was the only Labor member to do so. ‘I am’, he declared, ‘neither a rat nor a twister nor a renegade nor a traitor, and the men who say that do not speak the truth . . . I believe that loyalty to the Empire is infinitely more important than loyalty to any party’.Earlier,Adamson had pledged himself to enter the conscription campaign ‘with all my energy and . . . every inch of power I possess, because I believe that . . . the Empire should receive every assistance possible and that Germany should be beaten’.

In March 1917, he resigned his Assembly seat, hoping for Nationalist endorsement on that party’s Senate ticket. To his chagrin, H. S. Foll his former private secretary, was awarded the slot. Failing in a bid to win Paddington as an Independent Democrat in 1918 against J. A. Fihelly, a fiery, able, Irish-Australian, Catholic anti-imperialist, Adamson was rewarded with the top position on the Queensland Nationalist Senate ticket in 1919, and another consolation prize, a CBE. Elected in December 1919, he served until his death.[5]

Adamson’s career in the Senate was a tragic anti-climax to his pre-1916 enthusiasm and promise. Out of sympathy with the hard men of the Nationalists, feeling that the events and consequences of the war had irreversibly changed the social, economic and political landscape for the worse, Adamson, depressed and in chronic ill health, made few major speeches during his Senate term. Speaking on the budget in 1920, he said: ‘If, in the course of a few months, I am not sufficiently restored to health . . . I shall be quite prepared to allow some one else to take my place’. He bemoaned the fact that the Government was ‘placed in a very awkward and extraordinary position’ and that men were ‘demanding high wages and reduced hours of employment, instead of endeavouring to produce more, and thus lighten our terrific burden’. He continued: ‘Australia is now a nation . . . and the soldiers who fought for us, are responsible for Australia gaining national status’. Thus he thought that defence within the ‘great Commonwealth of nations’, should be a national priority, and that one of the ‘best ways to spend the money of the Commonwealth’ was ‘to seek to cement and solidify the connexion between Great Britain and ourselves’. He considered that this was ‘the only way the White Australia policy can be kept intact’. Pleading for the retention of the Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration and for increased British immigration, Adamson concluded his speech with a heartfelt plea for social unity, the ‘progress and safety of Australia, and the unity of the British Empire’. Later, during the debate on the War Precautions Act Repeal Bill, Adamson supported the retention of penal clauses to deal with those ‘who are prepared to adopt unconstitutional methods to promote disloyalty and revolution’.

Apart from concerns for the welfare of ex-servicemen, he made only one more speech in the Senate, that on the Public Service Bill on 4 November 1921. His concluding remarks disclosed an agony of mind and spirit: ‘the last fourteen months . . . have been terrible months to me . . . only I know how terrible they have been. I want to do what I can in the future for the country that has done so much for me . . .’.[6]

It was not to be. On 2 May 1922 Adamson fell in front of a train at the Hendra Station, Brisbane. Suicide was a possibility, but so was disorientation resulting from an agitated and depressed mental state. Accorded a state funeral at the Albert Street Methodist Church, attended by an eclectic mix of dignitaries, his wife, two sons, John and Norman, and four daughters, Alice, Minnie, May and Amy, he was buried in Toowong Cemetery. One daughter had predeceased him.[7]

Adamson was a civilian casualty of World War I. His brief contribution to the Senate should not obscure either his previous contribution to Australian public life, or those tragic conflicts between social justice and industrial militancy, between ‘Lion and Kangaroo’, between the ethic ofProtestant ‘improvement’ and restraint, and the needs of Irish-Australian Catholics.

In the end, he was unable to reconcile these forces: others did, he didn’t.

[1] Martin Sullivan, ‘Adamson, John’, ADB, vol. 7; Charles Arrowsmith Bernays, Queensland—Our Seventh Political Decade, 1920–1930, A & R, Sydney, 1931, pp. 334–6; Worker (Brisbane), 25 February 1911, p. 6; Boote Papers, MS 2070/1/3, NLA; QPD, 3 October 1916, p. 1037, 2 August 1911, p. 400.

[2] QPD, 20 July 1911, p. 167, 21 November 1911, p. 2292, 2 August 1911, p. 392; Charles Arrowsmith Bernays,Queensland–Our Seventh Political Decade, pp. 334–6.

[3] D. J. Murphy (ed.), Labor in Politics: The State Labor Parties in Australia 1880–1920, UQP, St Lucia, Qld, 1975, p. 178; QPD, 3 October 1916, p. 1037; Brisbane Courier, 15 March 1918, p. 7.

[4] QPD, 2 August 1911, pp. 394, 399, 400; Daily Standard (Brisbane), 23 January 1917, p. 6; D. J. Murphy, T. J. Ryan: A Political Biography, UQP, St Lucia, Qld, 1990, p. 223.

[5] Bernays, Queensland–Our Seventh Political Decade, p. 336; National Leader (Brisbane), 10 November 1916, p. 1; Raymond Evans, Loyalty and Disloyalty: Social Conflict on the Queensland Homefront, 1914–18, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1987, pp. 94, 98, 103–104;G. P. Shaw, ‘Patriotism versus Socialism: Queensland’s Private War, 1916’, Australian Journal of Politics and History, vol. 19, August 1973, pp. 167–78; QPD, 6 December 1916, p. 2375, 3 October 1916, p. 1038; Queenslander (Brisbane), 6 May 1922, p. 32.

[6] CPD, 19 November 1920, pp. 6727–30, 25 November 1920, p. 6970, 4 November 1921, p. 12466.

[7] Maryborough Chronicle, 3 May 1922, p. 5; Telegraph (Brisbane), 5 May 1922, p. 2; Daily Standard (Brisbane), 3 May 1922, p. 5; Queenslander (Brisbane), 6 May 1922, p. 32; CPD, 28 June 1922, pp. 12–14.

This biography was first published in The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, vol. 1, 1901-1929, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, Vic., 2000, pp. 133-136.